Our Bodies Made of Water

Our bodies made of water is an on-going research and representational endeavor that explores the relationship between people and water, probing how this entanglement shapes specific spatial and material choices made in the landscape.

From January - March of 2023, I conducted field research in small coastal towns within the Los Ríos and Los Lagos regions of southern Chile. Here I met with a diverse group of artisanal fishers from seaweed harvesters to crabbers to fisherpeople. From March - July of 2023, I traveled across the globe to Galicia, Spain to meet with mariscadoras (shellfish harvesting women) and other women working in the fishing sector in this region of Spain. This research was supported by Harvard University's Sinclair Kennedy Traveling Fellowship. Navigate to the extra bits & bobs page to read some published work.

... More to come

Below is a collection of images captured on 35mm film from my time abroad:

︎︎︎

Channelview, Texas

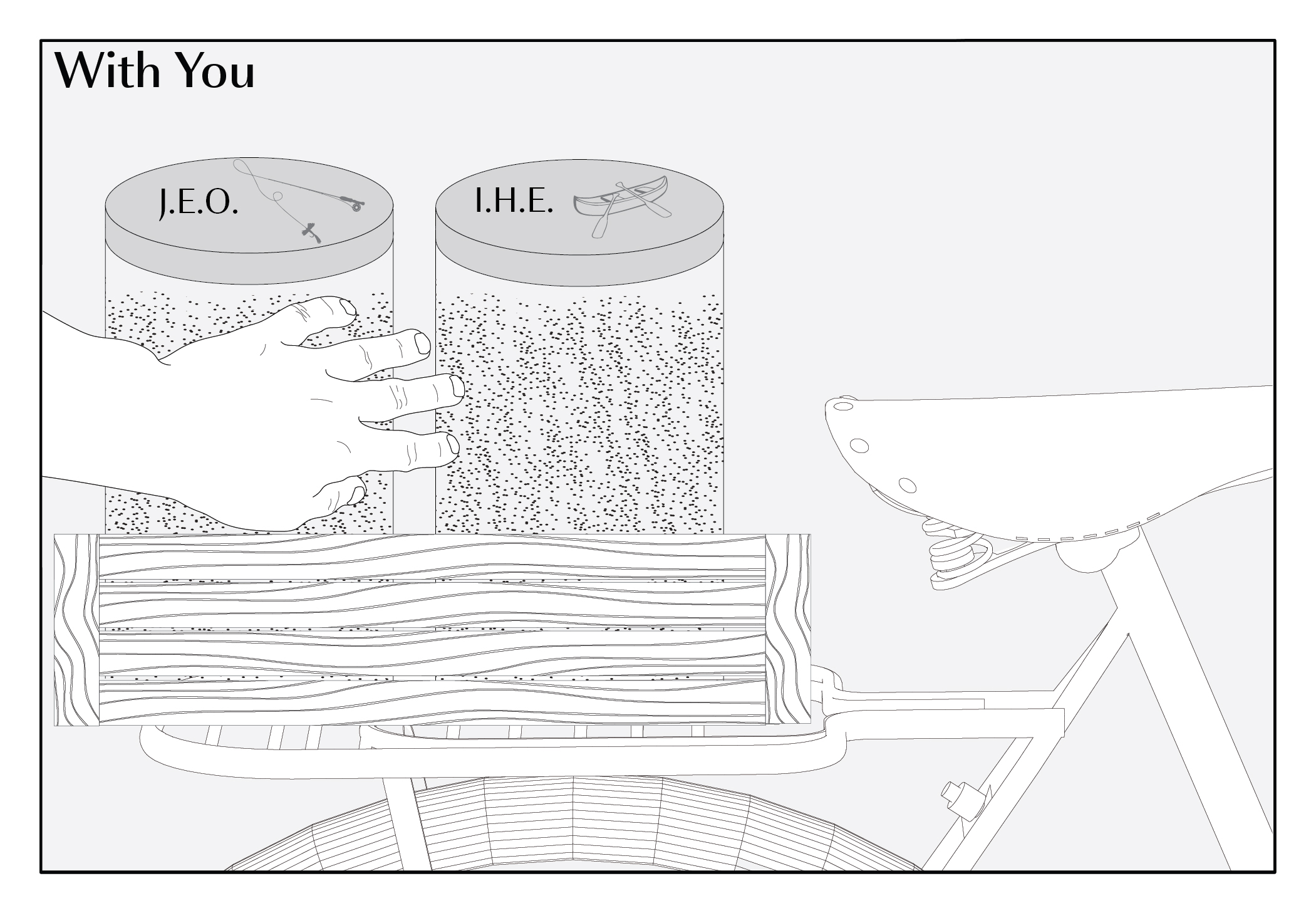

This Penny White Project continued to build upon the work of my final MLA design thesis, to cast a line in the san jacinto river, and offered insight into the deficiencies, and revelations, of online-research and the importance of embodiment as an ongoing practice in the field of Landscape Architecture.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

These guiding principles are what I carried with me throughout this project. By defining and naming these for myself, I was able to communicate more clearly with those I interviewed and met in the field. It provided clarity and allowed for rich conversations with “experts” on the study area and this particular Superfund Site. It allowed for us to share ideas and insights on how they understood their own work and allowed me to further reflect upon mine. Taking these theoretical musings and applying them to the realities of addressing contamination, storms, bureaucracy, and a project that has been in the works for over 13-years, allowed for them to evolve in ways I didn’t anticipate. This was a direct result of having conversations in the field.EMBODIMENT

Embodiment here refers to the way in which someone experiences, or sees, a place. It is a way of thinking that helps us visualize how we are both in the landscape and of the landscape, acting in relation to it, just as it acts on us as well. This concept draws upon the work of Setha Low and Astrida Neimanis. PLACE

Rather than thinking of place as a site with a defined boundary, what if we addressed place through the layered histories and experiences that make place. That make home. That hold memories.

That change.

STORM

A hurricane can be understood not only as a moment of instability, but as a moment of intensity that generates a closeness to water and a thickness of land. The storm is positioned as an experience that is lived. By detaching the storm from the moment of impact and the ‘destruction’ that it leaves behind, you gain a more nuanced understanding of how the storm is an agent of change, of bounty, and even, perhaps, a moment to celebrate and endure.REMNANT

The traces of people. An image of embodiment, of use, of location, of time, of activity, of positionality, of care. What they leave behind offers another way of seeing. Seeing someone. Understanding pieces of a moment, of a way of living. The passing of time. It’s not so much what someone may have forgotten or intentionally left in a place, but how pieces of them entangle with their surroundings - fishing line caught on telephone wires, shrimp shells piled up on the edge of a bridge, raw chicken juice rotting in the hot humid sun. ADVISORIES

Fences line the pits, documents and advisories build up in file cabinets off-site, signs are posted along the shoreline, and yet, people still fish in places that are defined as unsafe or dangerous. They still stop along the roadways to cast their lines, drop their nets, or wade into the water in search of food. Families gather each Sunday and catch their week’s worth of protein in a few hours - hours filled with laughter and play. These advisories are ineffective and distanced from the reality of how this area is used, experienced, embodied. What might an ‘advisory’ that builds in a better practice of observation, communication, correspondence, and advocacy look like?SOFT

Softness does not sit in contrast to something that is “fixed” or “rigid” or “defined”. It is a part of it. Softness refers to the inevitable cracks, fissures, and breaks in rigidity that allow for growth to happen. This is translatable between everything from materials to emotions to our bodies. Softness is a seed that lands in the soil after a storm and begins to grow miles from where it came. Softness is the hug you get when you lose someone or something in a storm. Softness is a crack in our working hands and feet. Incorporating more softness in our work is paramount. ENTER

Our bodies and the things that surround us are registers of change. We see changes in materiality over time - the degradation of materials, the erosion of the shoreline, the wrinkles in our skin. We see it, but do we honor it? Do we plan or design with it? Imagine entering into the water and sensing the change in the tide on your skin. The discrete changes in water level becomes a register of the dynamics at play around you. It’s about drawing attention to these moments of noticing, of sensing, of feeling, of measuring that are built within us - Our capacities are endless. CHANGE

The dynamics of a place. Everything is always undergoing change. It may be visible, it may be obfuscated. Regardless of its ability to be measured or quantified, change happens. It may not be able to be anticipated, but it is embodied. The fisherpeople know this. They plan their days around tidal fluctuations, the migration of fish, the visible, and the invisible. WATER

Water is a conduit and mode of connection. We are made of it. It offers us the buoyancy we need to keep going. As Astrida Neimanis argues, there are other ways of understanding water as something that has the power to connect us. It shapeshifts, it cycles, it transports, it gives and takes life. It is both simultaneously opaque and transparent. CAST

A moment with intention. A release. An activity that has both solitude and community built in. Casting a net or a baited hook defines a place. It is an action that brings people together. Built within it is sensing, location, patience, excitement, and conversation. It keeps you still but with enough attempts, keeps you moving. It is an action that binds your hands to something in the water. Something you can’t yet see but wait to feel. Most importantly, it brings people together. It brings people back to the same spot that offers food, solitude, and community. It weaves disparate lives together over a common goal.

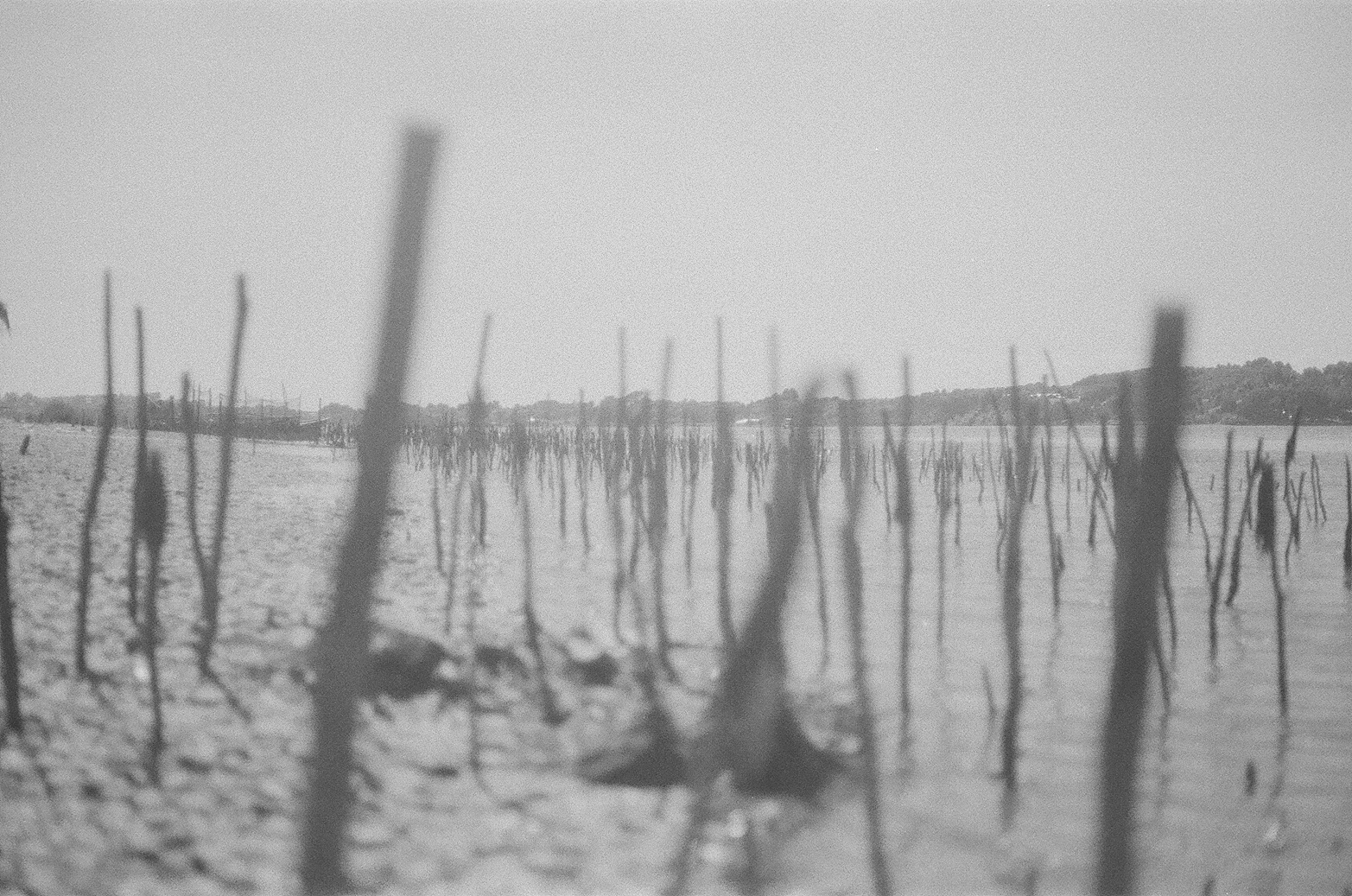

Below are some of the photographs captured during a week-long site visit to the Houston, Texas area in July of 2021.

︎︎︎

to cast a line in the san jacinto river

Advised by: Emily Wettstein

This thesis addresses agency of the body, of space, and of marginalized lifeways for subsistence fishers near Houston, Texas. It does so through a feminist approach that centers processes of change, instability, and emergence as mechanisms to leverage the fisher community’s embodiment of the landscape through the design of a near-future fishing spot along the San Jacinto River.

This project is designed through hurricanes; Understood

not only as a moment of instability, but as a moment of intensity that generates a closeness to water and a

thickness of land.

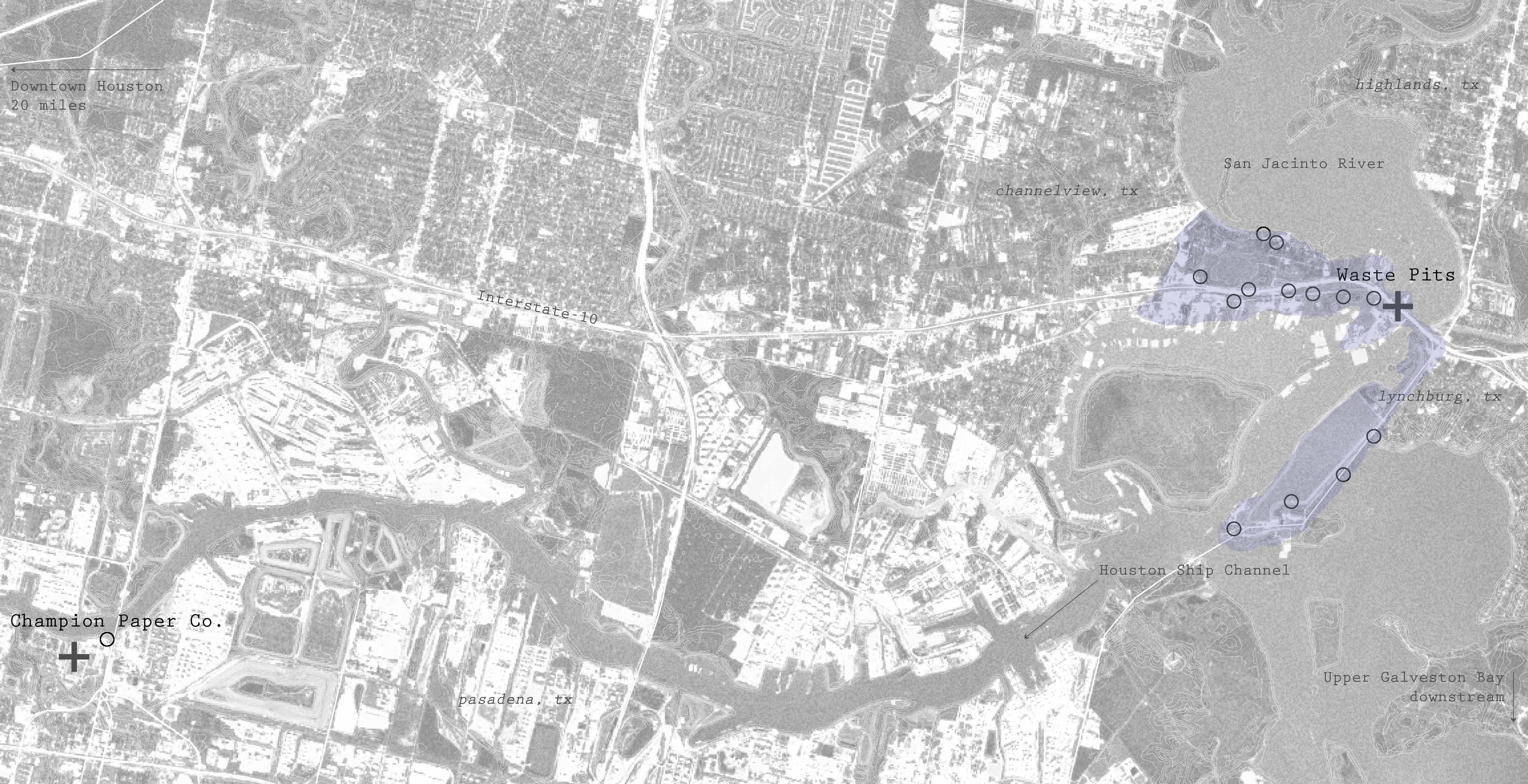

The storm can be understood here as the event to design through - and therefore - the site can be understood not as ‘site’ with a defined

boundary, but as a place layered with histories. Although there is a ‘site’, the San Jacinto River Waste Pits, located roughly twenty-miles east of Houston Texas, it’s history as a toxic dump for the Champion Paper

Company in the 1960s actually extends beyond its defined boundaries and into the flesh of fish, the sediment of the river, and the people that

cast their lines into the water in search of food.

In this project, the storm is positioned as an experience that is lived. By detaching the storm from the moment of impact and the ‘destruction’ that it leaves behind, you gain a more nuanced understanding of how the storm is an agent of change, of bounty, and even, perhaps, a moment to celebrate and endure.

In this project, the storm is positioned as an experience that is lived. By detaching the storm from the moment of impact and the ‘destruction’ that it leaves behind, you gain a more nuanced understanding of how the storm is an agent of change, of bounty, and even, perhaps, a moment to celebrate and endure.

Rather than thinking of place as a site with a defined boundary, what if we addressed place through the layered histories and experiences that make place.

That make home. That hold memories. That change.

That make home. That hold memories. That change.

One of these histories has an explicit relationship to the body.

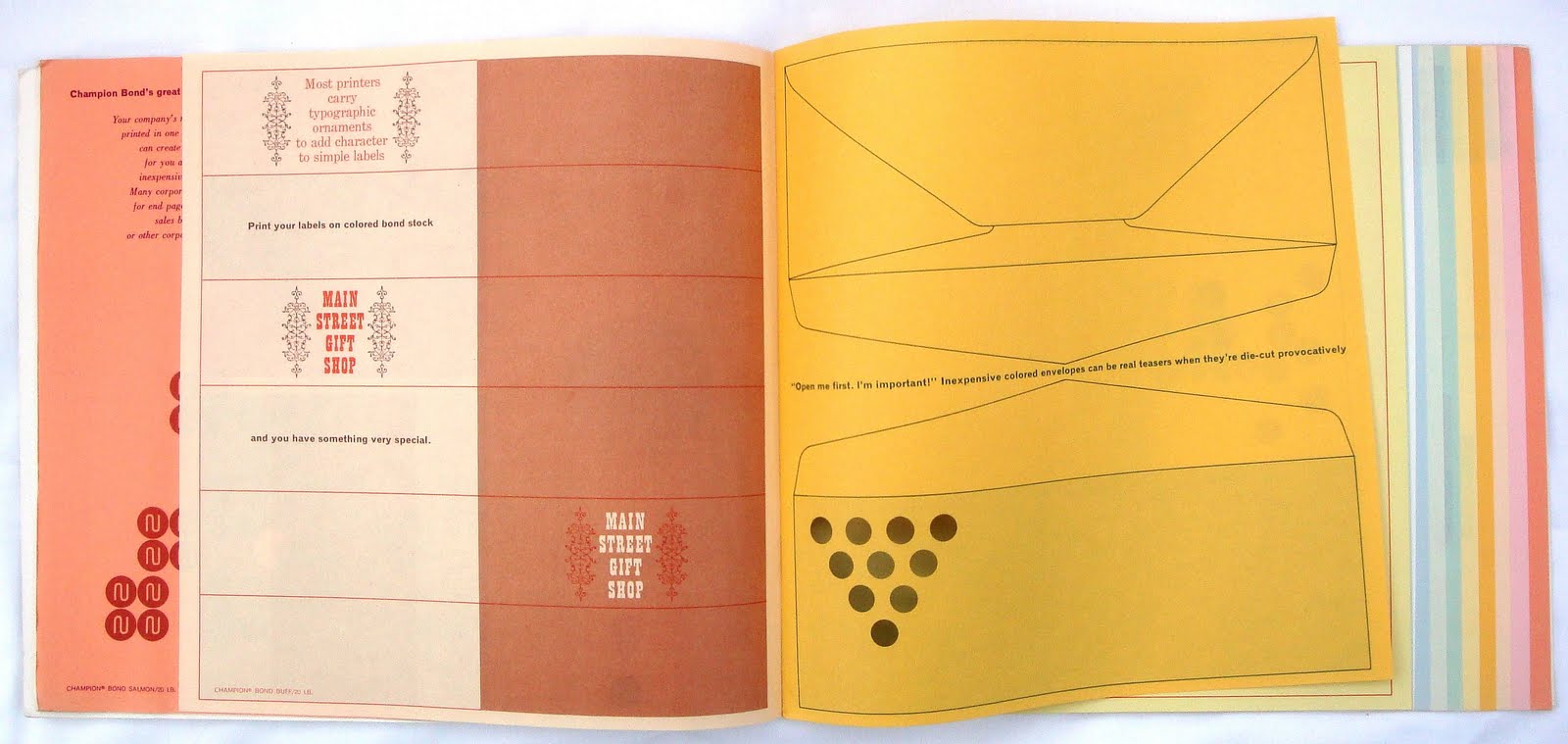

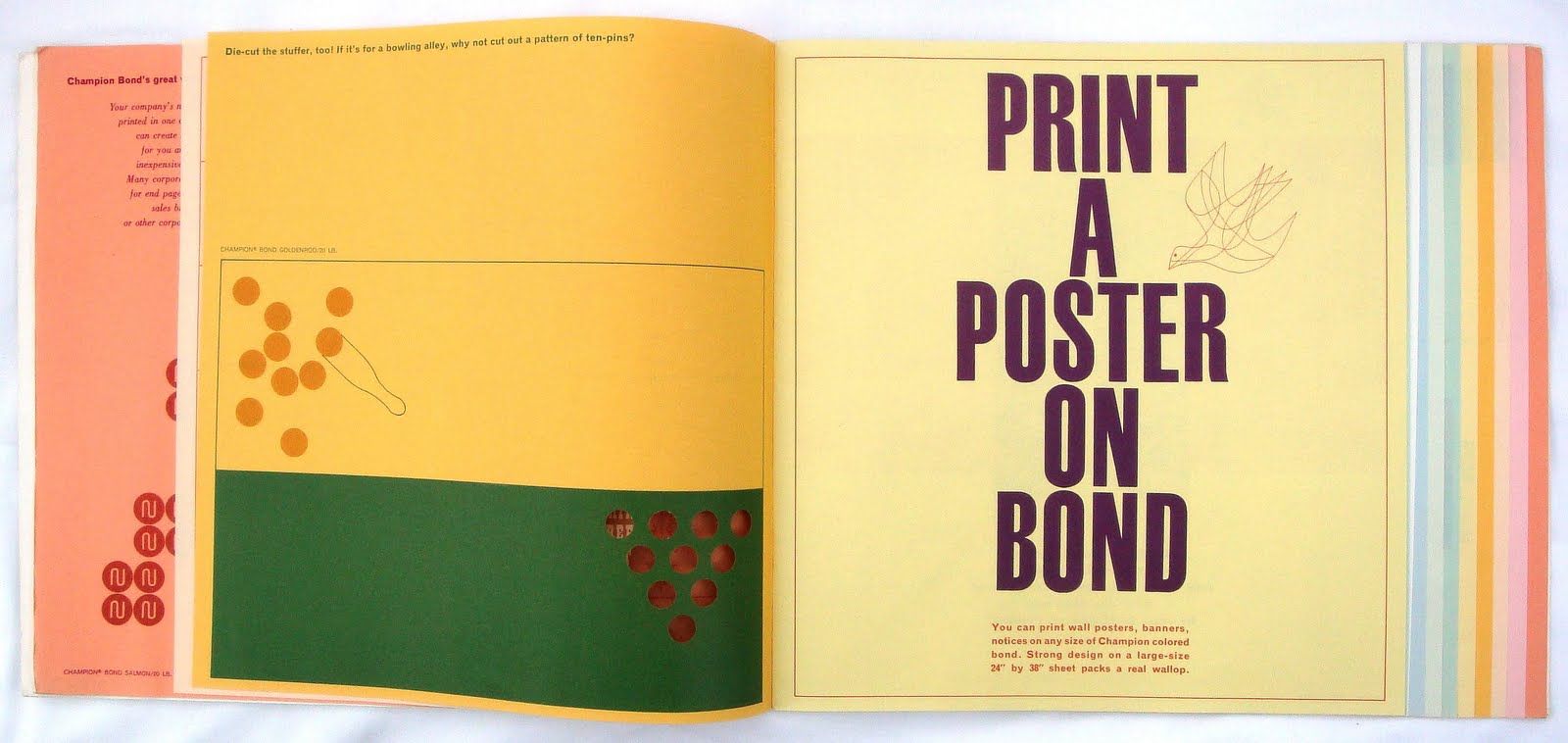

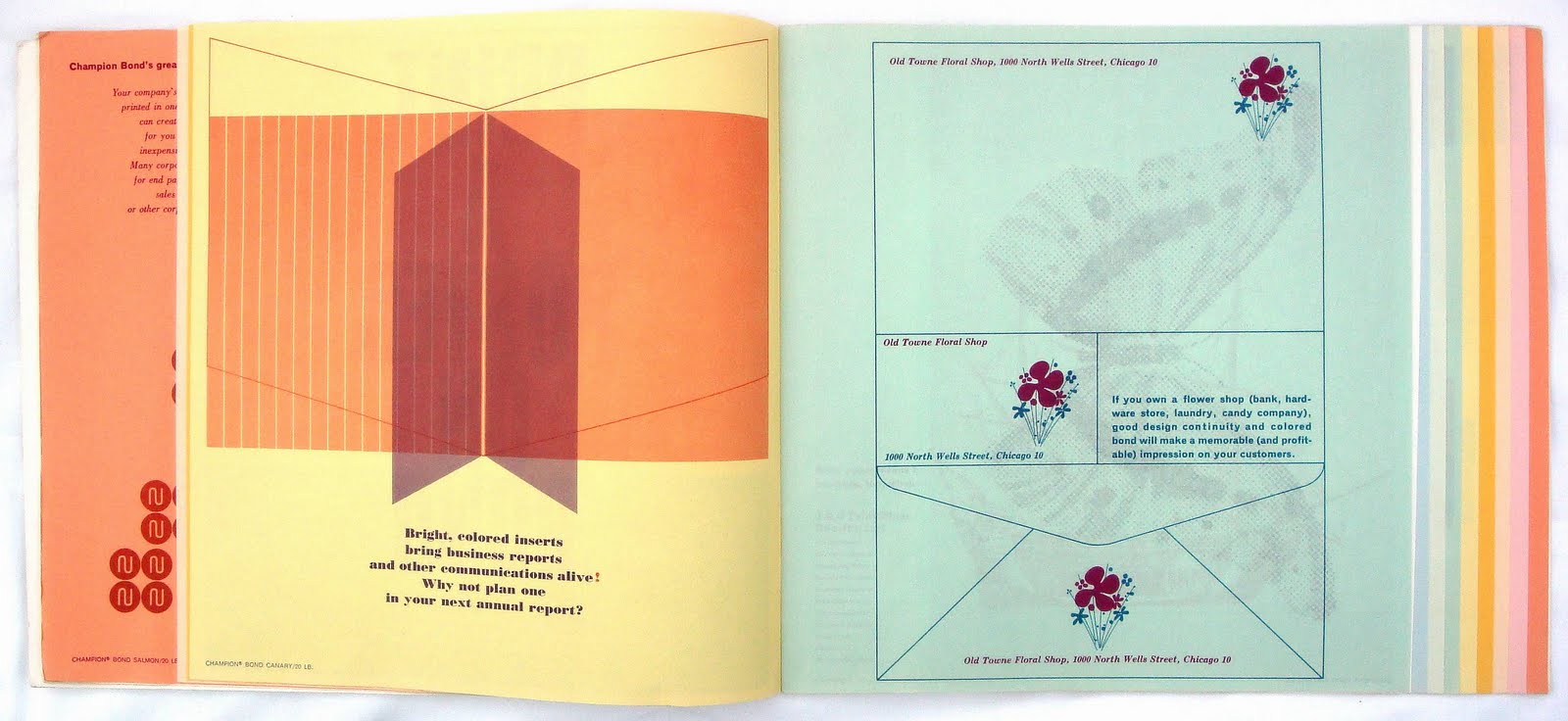

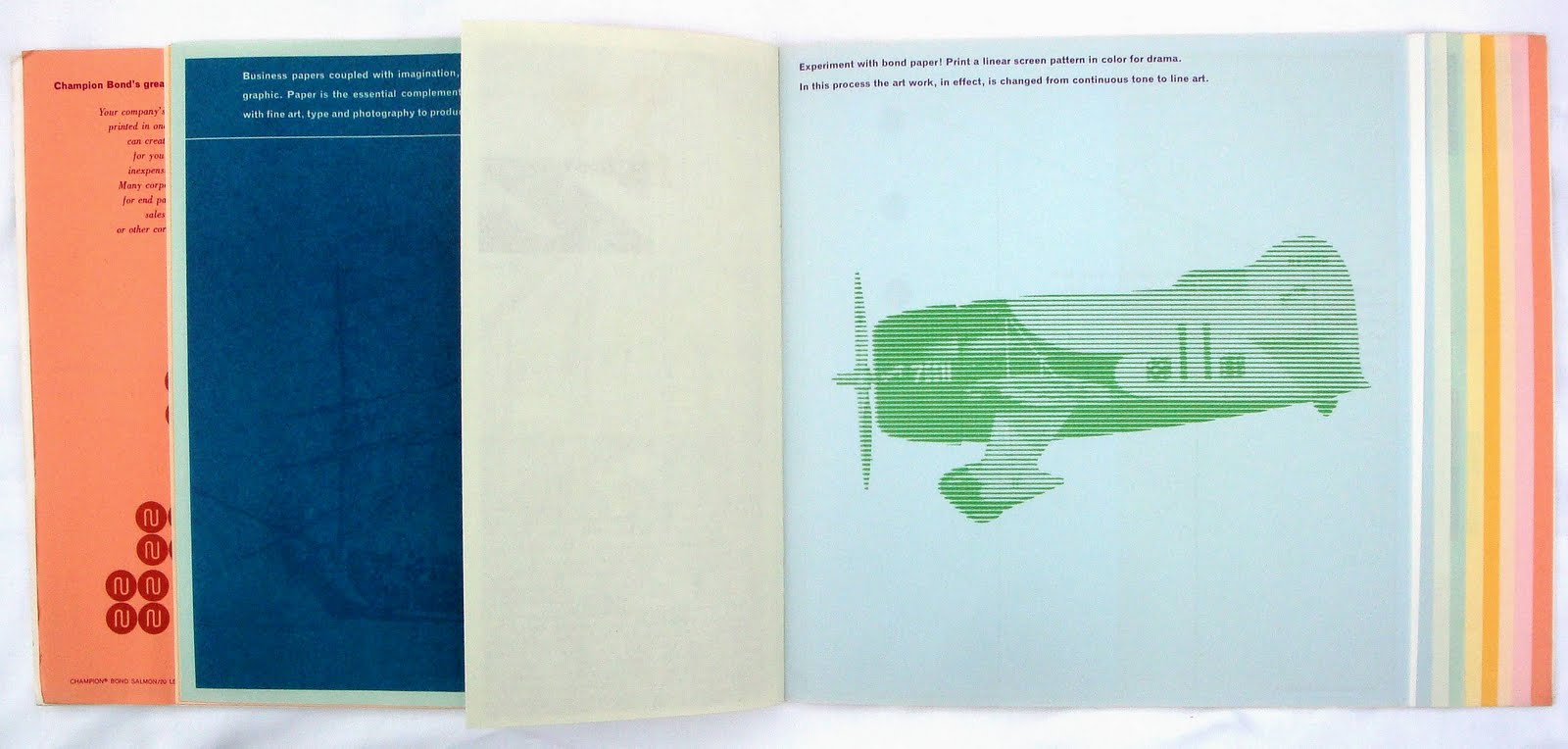

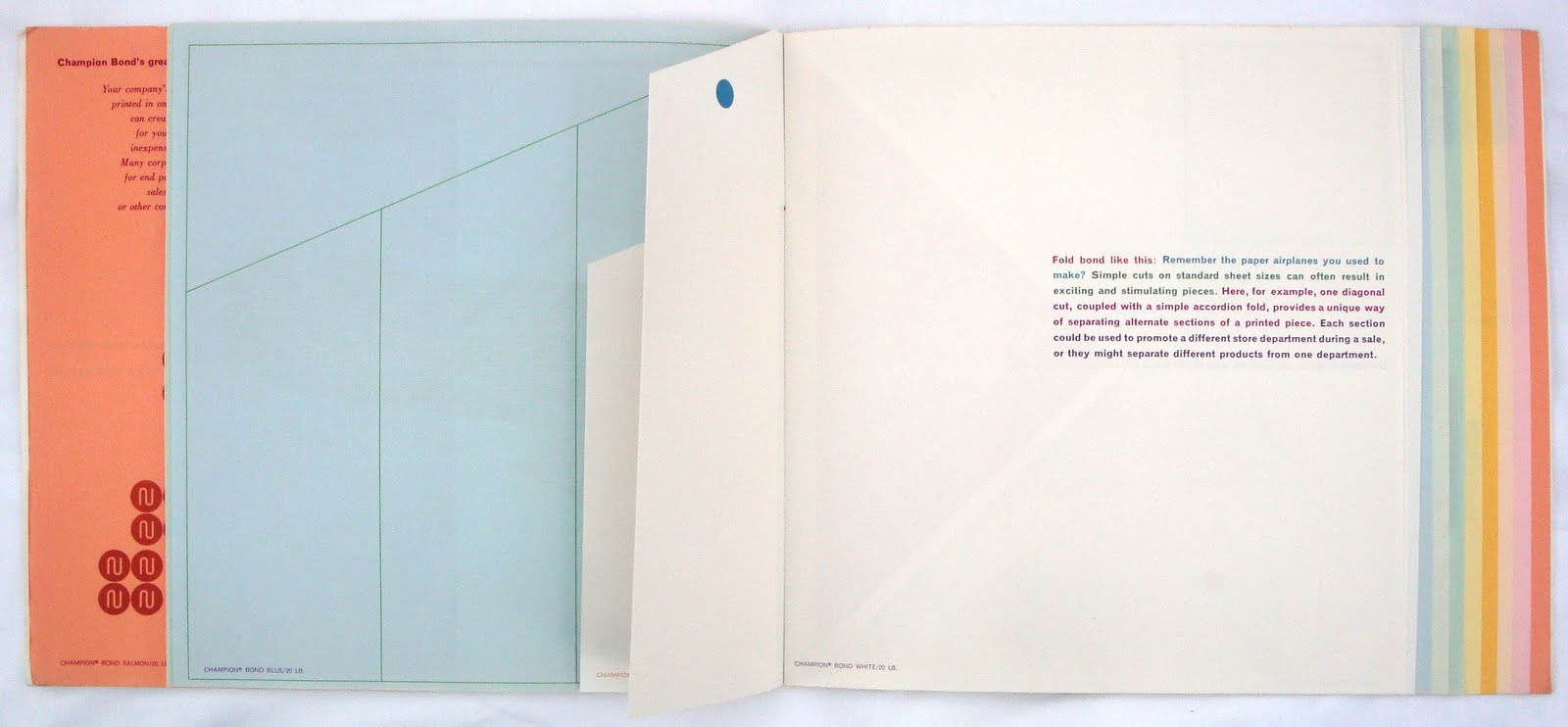

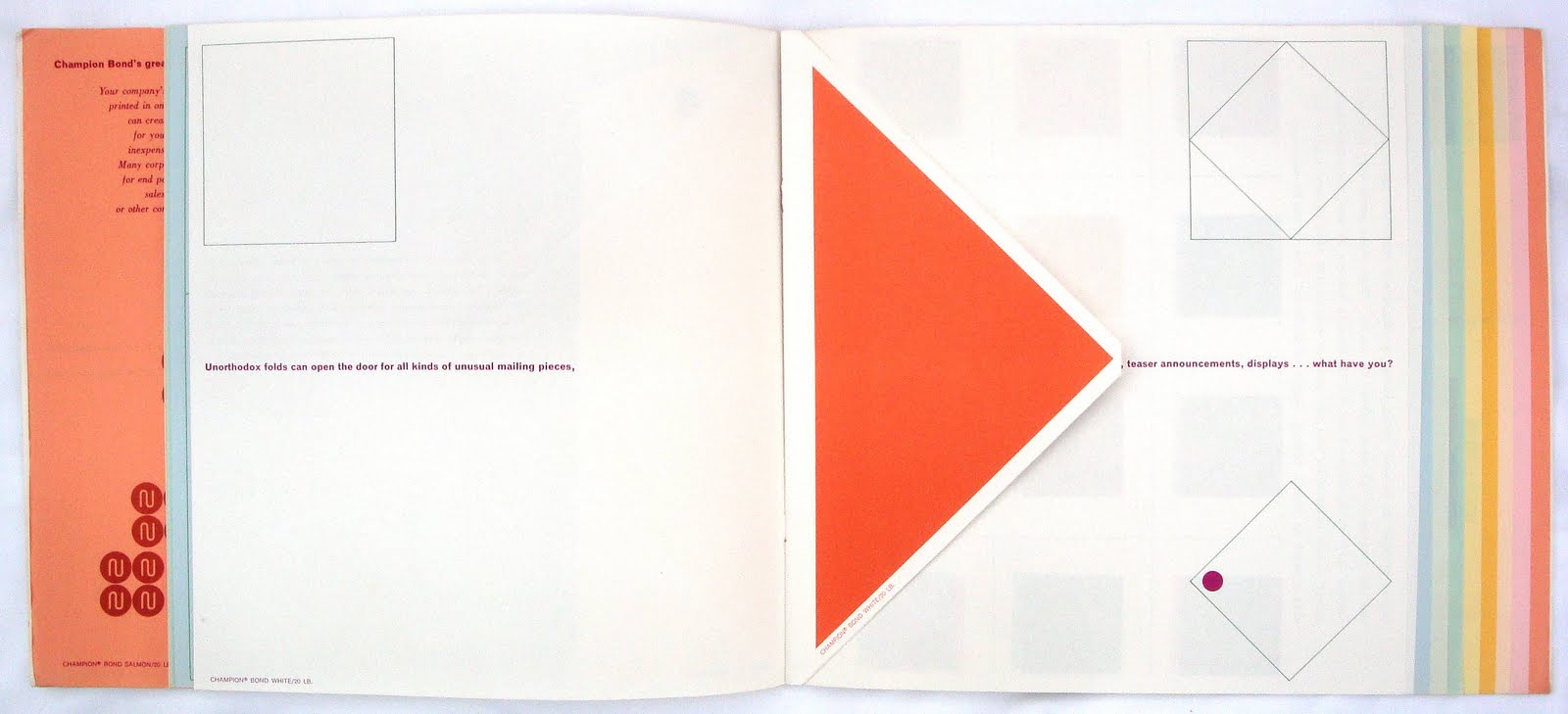

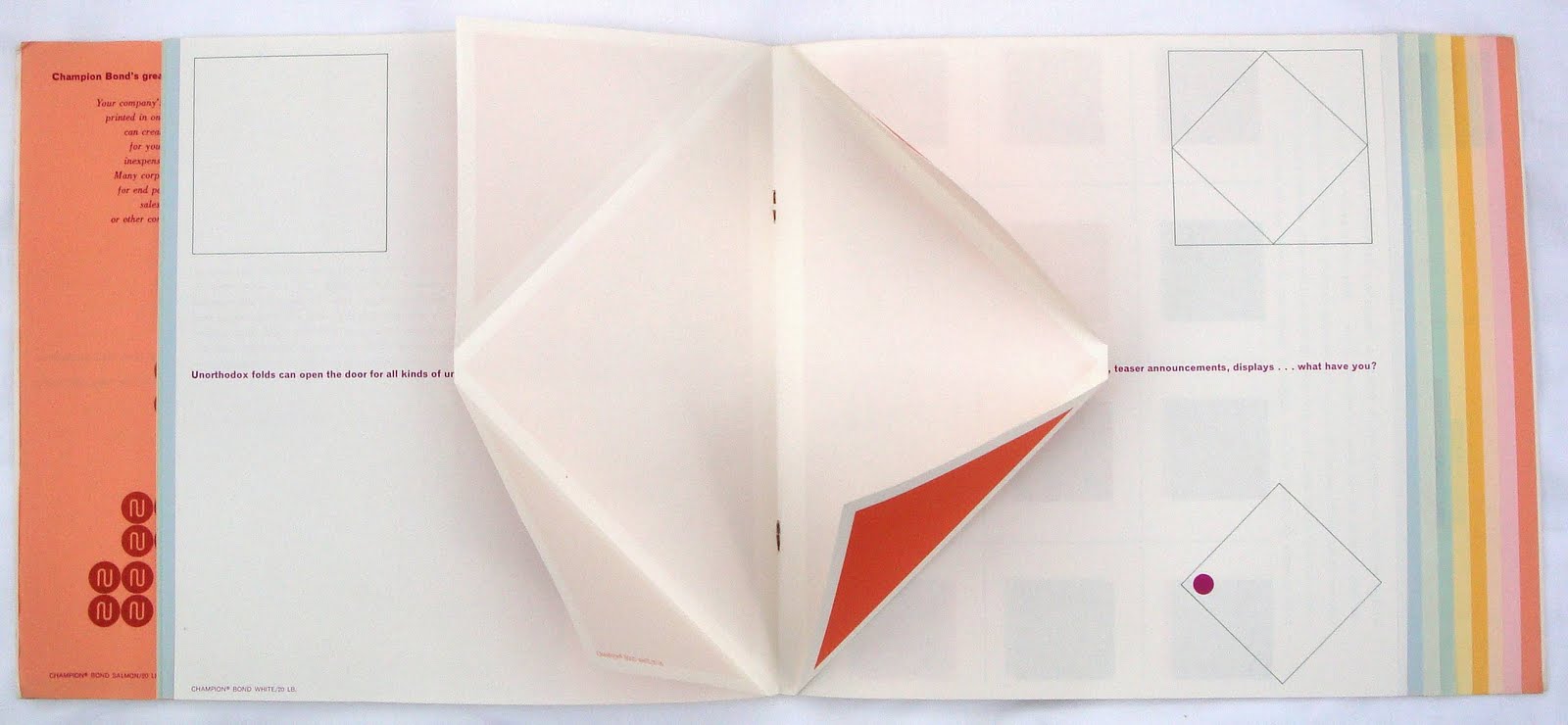

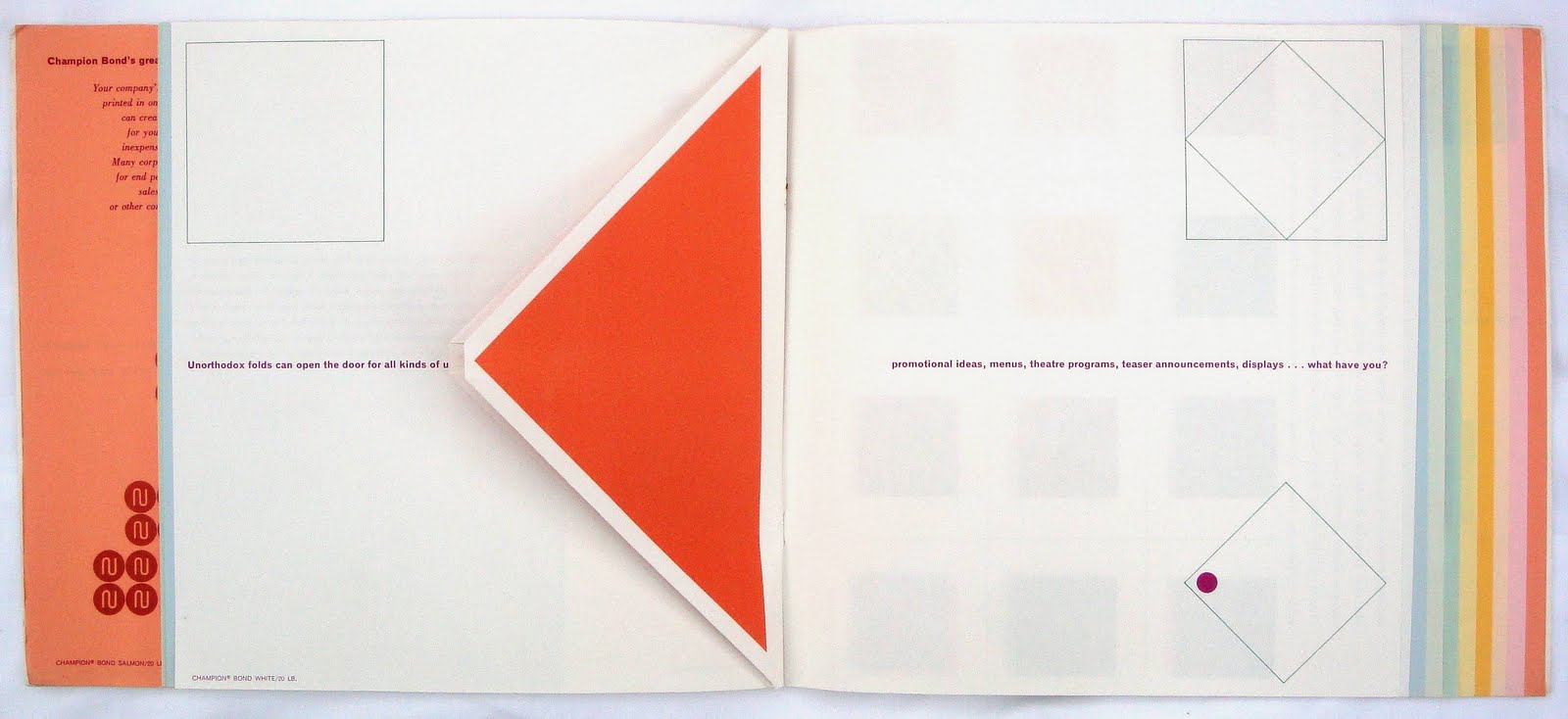

In 1965, the Champion Paper Company, located on the Houston Ship Channel, was commissioned to produce a brochure of paper and ink samples, called the Imagination Series. The volumes took an entire year to develop and offered bound research and inspiration for designers.

The popularity of this series thrusted the Champion Paper Company to the top of the market for paper production. As production soared, so did the waste. The San Jacinto River Waste Pits were created in 1965 to dispose of wastewater from the local paper company. Each day, tens of thousands of gallons of wastewater and sludge was transported by barge along the Houston Ship Channel to the newly formed, unlined, waste pits at the mouth of the river. This waste, contaminated with dioxins and furans, pose significant risk to the adjacent community, fish, and wildlife.

In 2008, the site was listed as an active Superfund Site and was closed to the public. The EPA has a current remediation strategy for the Pits that carve deep scars into the land at the Northern and Southern Impoundments. My strategy is to use this EPA cleanup as a design opportunity - To weave in the storm, the body, and the lives of those that enjoy this place.

NORTHERN IMPOUNDMENT

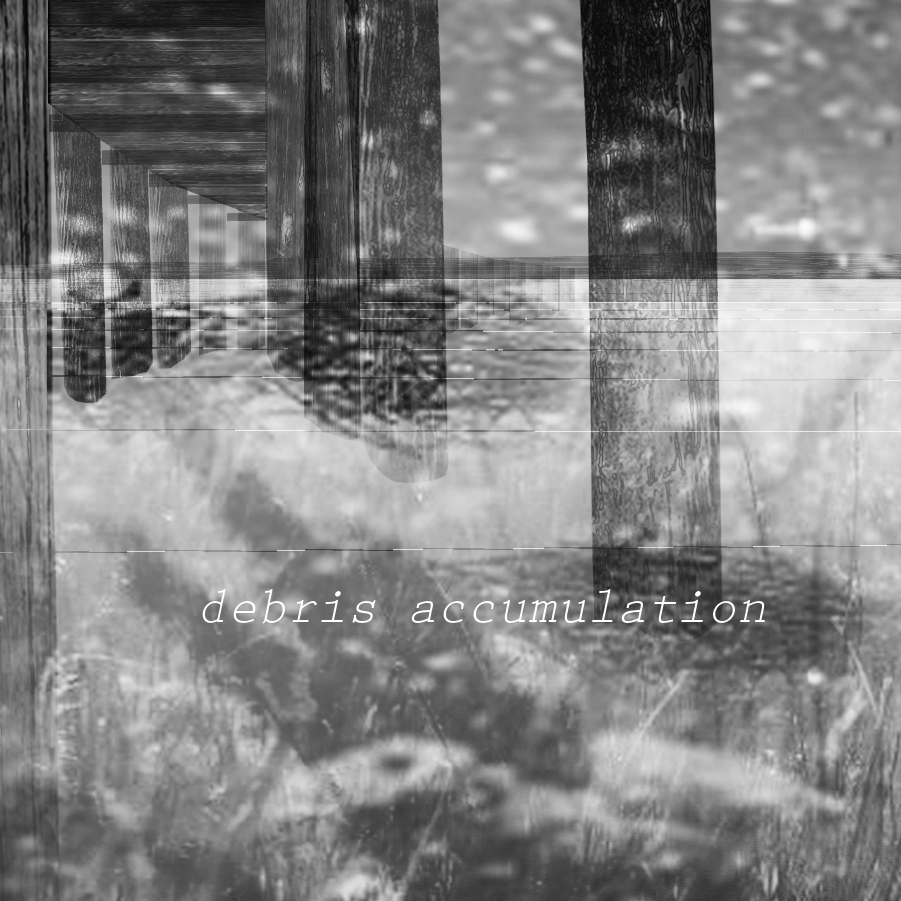

At the northern impoundment, sequence, indeterminacy,

and embodiment informs the design of a fishing pier network that extends the body over the deep river channel,

where the cast from a fishing rod extends far beyond the

shore.

![]()

![]()

Through reframing existing materials and working with dynamic processes, this design traces how people measure this place.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

As you move down the steps of the Round Pier, you must enter into the river, wading into the warm shallow brackish water to reach the long pier. This act of wading into the river is intentional – subsistence fishers often rely on the shoreline to fish from, only moving as deep into the water as their body, and the river, allows. The act of lowering oneself into the shallows, moving under the rounded pier, and out onto the long pier, is an act of agency over the body.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The power in gaining access to the deep river channel that you couldn’t reach before is embodied in Long Pier. The memories of the storms that have passed become visible as the piers are constructed over time. These piers hold memory, change, and materials of the hurricanes, as well as the lives of those that fish from them. These piers attempt to balance personal trauma with community construction as an act of shared memory.

Through reframing existing materials and working with dynamic processes, this design traces how people measure this place.

As you move down the steps of the Round Pier, you must enter into the river, wading into the warm shallow brackish water to reach the long pier. This act of wading into the river is intentional – subsistence fishers often rely on the shoreline to fish from, only moving as deep into the water as their body, and the river, allows. The act of lowering oneself into the shallows, moving under the rounded pier, and out onto the long pier, is an act of agency over the body.

The power in gaining access to the deep river channel that you couldn’t reach before is embodied in Long Pier. The memories of the storms that have passed become visible as the piers are constructed over time. These piers hold memory, change, and materials of the hurricanes, as well as the lives of those that fish from them. These piers attempt to balance personal trauma with community construction as an act of shared memory.

SOUTHERN IMPOUNDMENT

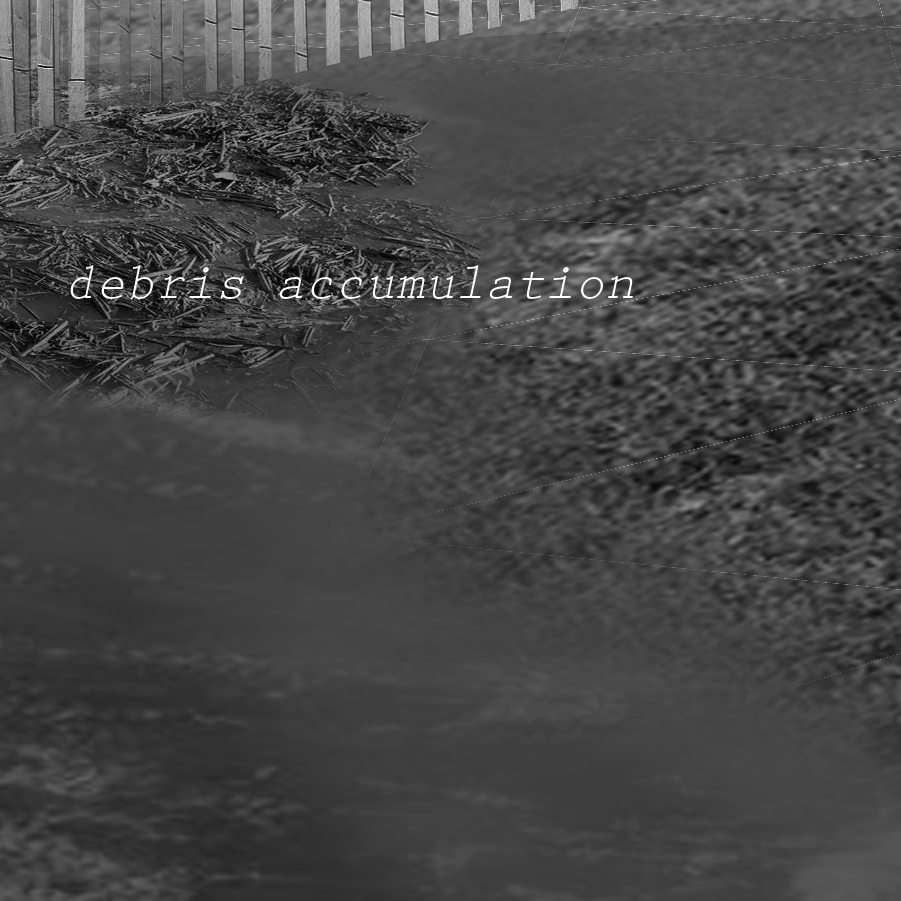

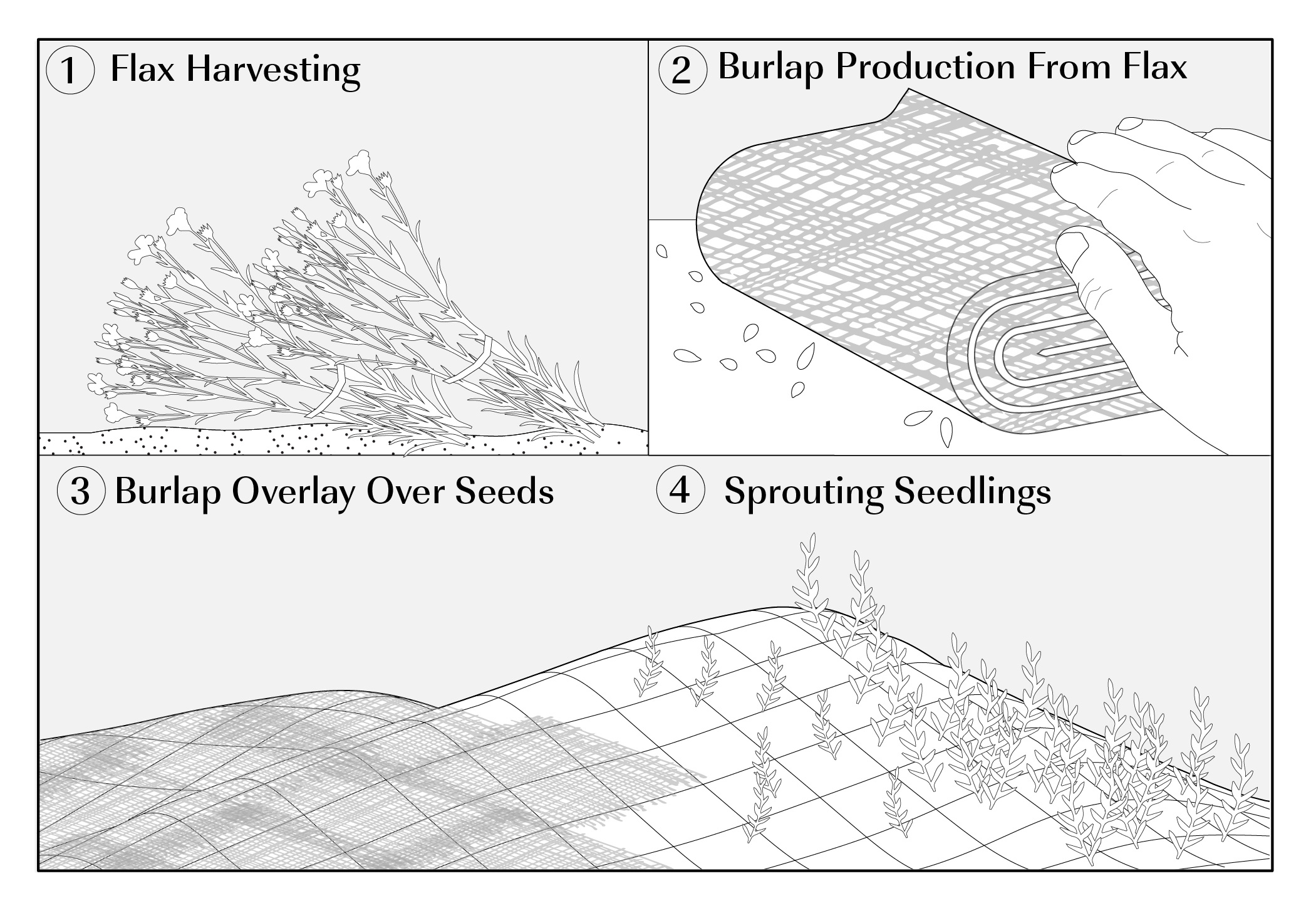

Using the existing language of the EPA’s strategy at the

Southern Impoundment, I propose a different type of silt fencing to guide sediment accumulation that in turn,

promotes emergent vegetation to take hold.

Unlike the northern impoundment, this process is not integrated into the EPAs remediation plan, but emerges post-remediation as a means to mend the scars they left behind. These silt fences are spaced in rows that let the storm surge in at varying degrees. The tighter their spacing, the more accumulation of sediment from the river, the more emergent vegetation that grows thereafter. The emergence of the five species of plants then becomes a register of the strength and age of the storms.

These fences are dynamic, shifting over time to collect sediment as ground and vegetation builds up around them. They shift in relation to the storm - As the thickness of the land builds, the water shifts around it. The dynamics of this place are in flux, a call and response to the needs and wants of this place. The accumulation of this sediment on land slows the receding water, depositing more sediment in the shallows off-shore.

WATER

In this project, the power of water is also positioned as a conduit and

mode of connection. The design does not stop at the shoreline, it digs deep into the river and builds upon existing fluid dynamics.These four glimpses into the water illuminate this.

ENTER

As the water laps at the pilings, so too does it lap at the

body. This design measures discrete changes in tide, in degradation, and in accumulation as it relates to the body. Your legs become a register for the slight change in grade as the long pier slowly moves up and out of the water, only noticeable by the water

slowly receding down your calves.

As storms move through each year, wooden planks are replaced by the hands of the community. The piers

maintenance therefore becomes a directory of community value.

Now that one can reach deeper waters and bigger fish, the fishing line

protects the body from the accumulated toxins that still remain in the flesh of the fish that they catch. Fishing line stored on site, free for all

to use, is calibrated for the fish migrating through, and the maximum weight of the fish that could safely be consumed. This line embeds the

advisory into the tool, rather than in signage; snapping when the weight of the fish is too heavy to eat safely that day.

The Round Pier registers the tidal range of the river by wetness on the wood, while your body feels it as you wade into the water.

These moments are intentional and build whole bodily agency over this place.

Your line has been cast, the sharp snap of the sunlight captured on its translucent wire indicates a strong wind - the dance of the line. The line fl oats out, suspended in air, twisting, warping, but always with a strong direction. Each cast has a goal. A destination. The last sound to hit the water - a plop -

before it goes silent below the surface of the river. You cast near to the pier - your goal is Red Drum

today.

The sound of fishing from this pier builds in anticipation of the storm. The low hum of conversation filled with moments of silence, the clicking of the reel, the snap of the line, the oohing and awing, the creaking of the boards as people pass, coolers full, coolers empty. The lapping of the water as it hits the wooden piling adorned with its previous life. Your own stillness, in thought, in your body, puts you in a trance as you wait for a tug on the fi shing line. You look forward to these moments, to when you cast a line deep into the San Jacinto River.

![]()

The sound of fishing from this pier builds in anticipation of the storm. The low hum of conversation filled with moments of silence, the clicking of the reel, the snap of the line, the oohing and awing, the creaking of the boards as people pass, coolers full, coolers empty. The lapping of the water as it hits the wooden piling adorned with its previous life. Your own stillness, in thought, in your body, puts you in a trance as you wait for a tug on the fi shing line. You look forward to these moments, to when you cast a line deep into the San Jacinto River.

The Dimensions of Touch

Advised by: Sierra Bainbridge, MASS Design Group

Community Partners: Galveston Bay Foundation, Shriner’s Hospitals for Children

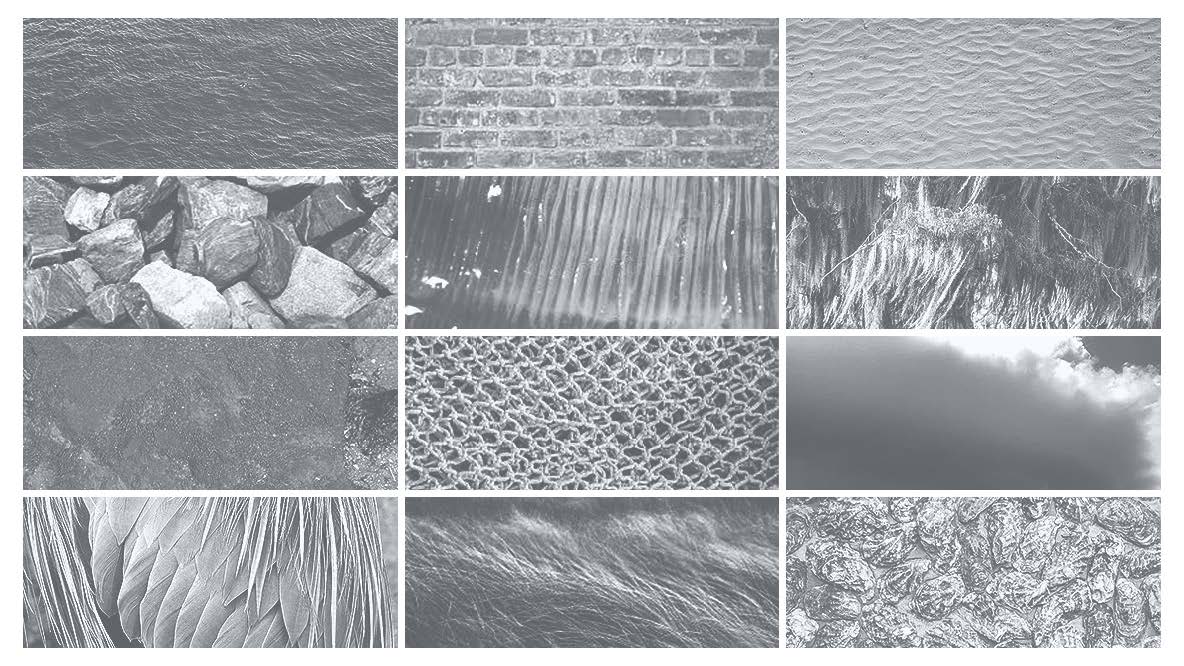

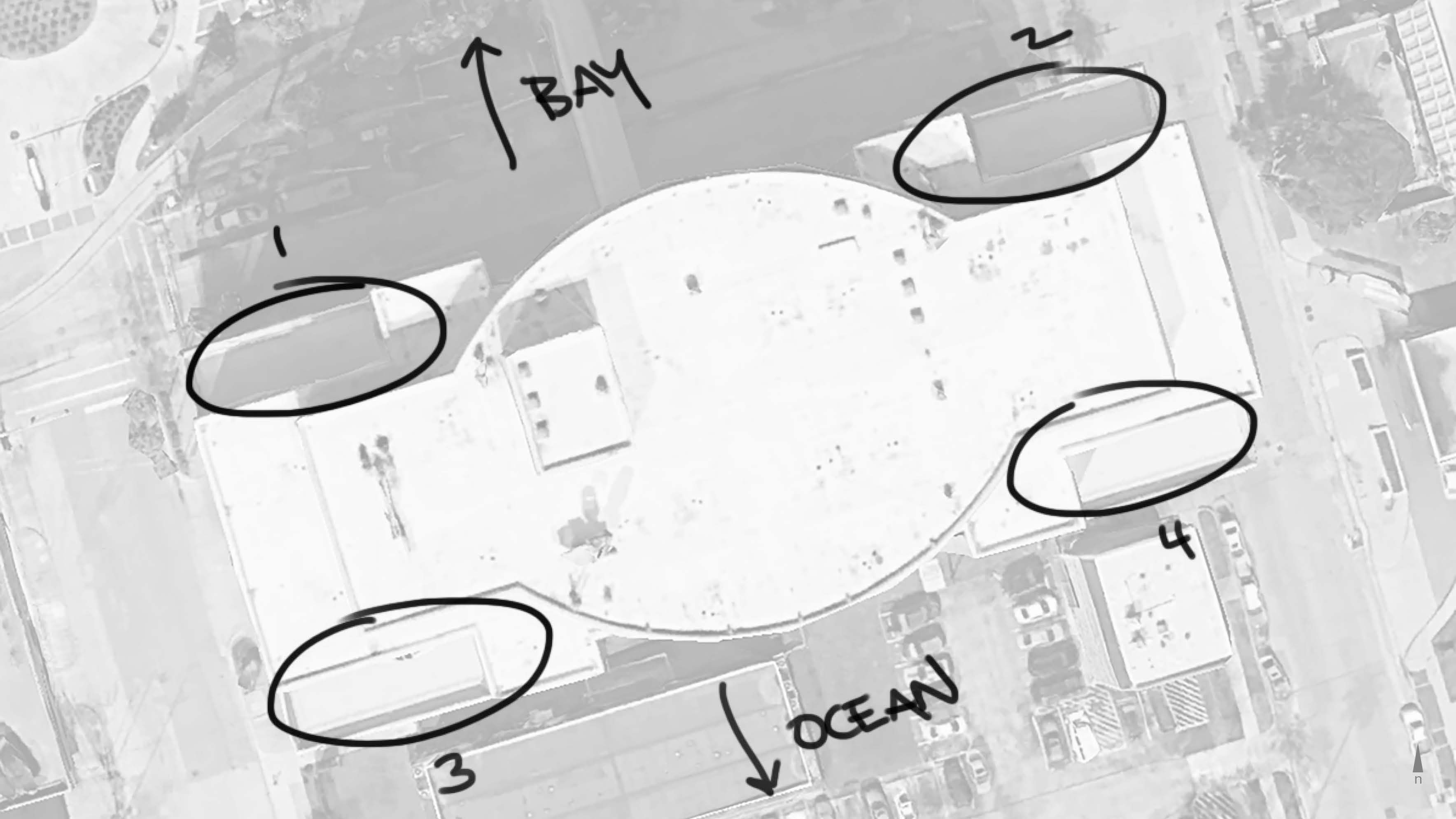

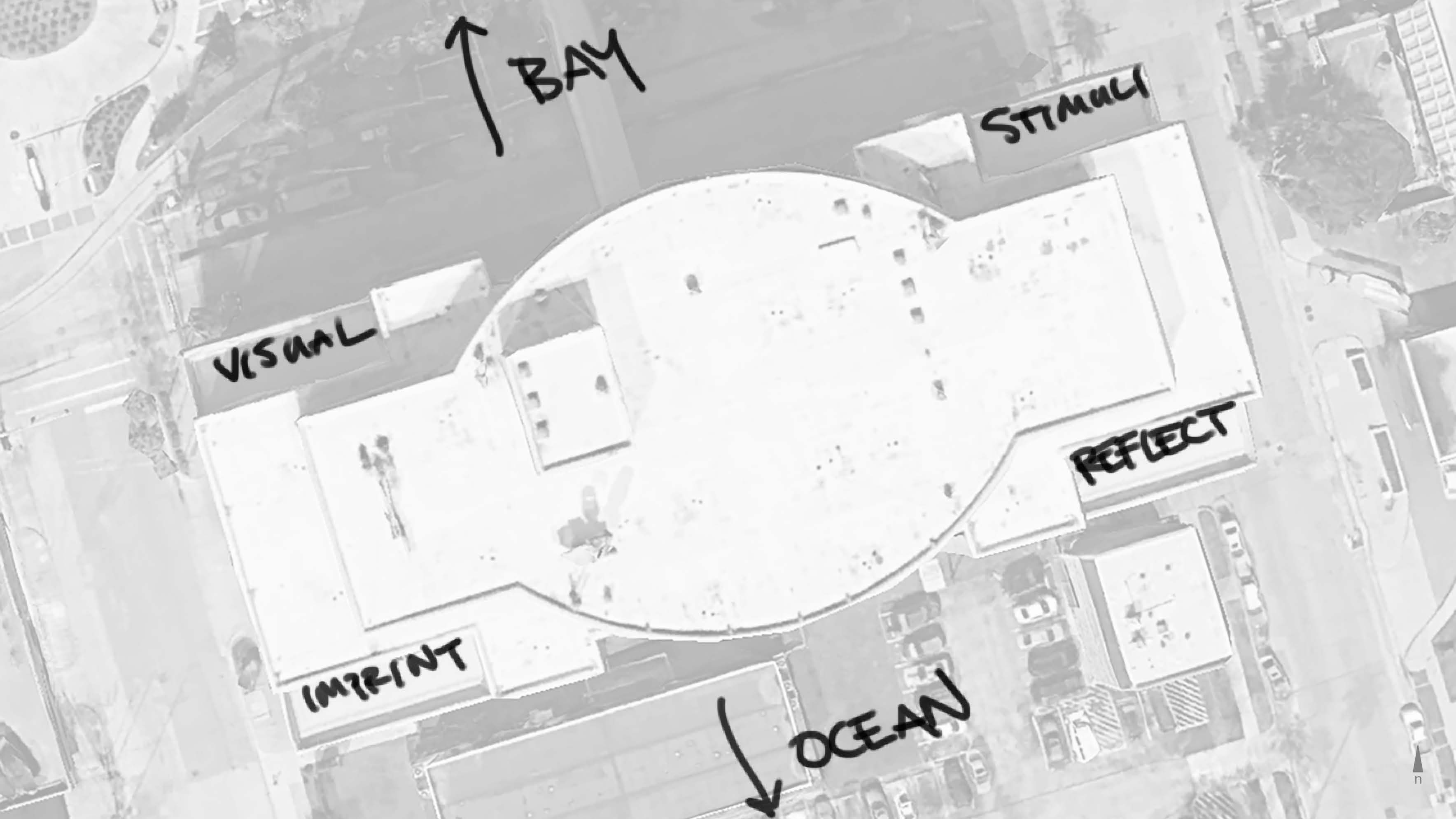

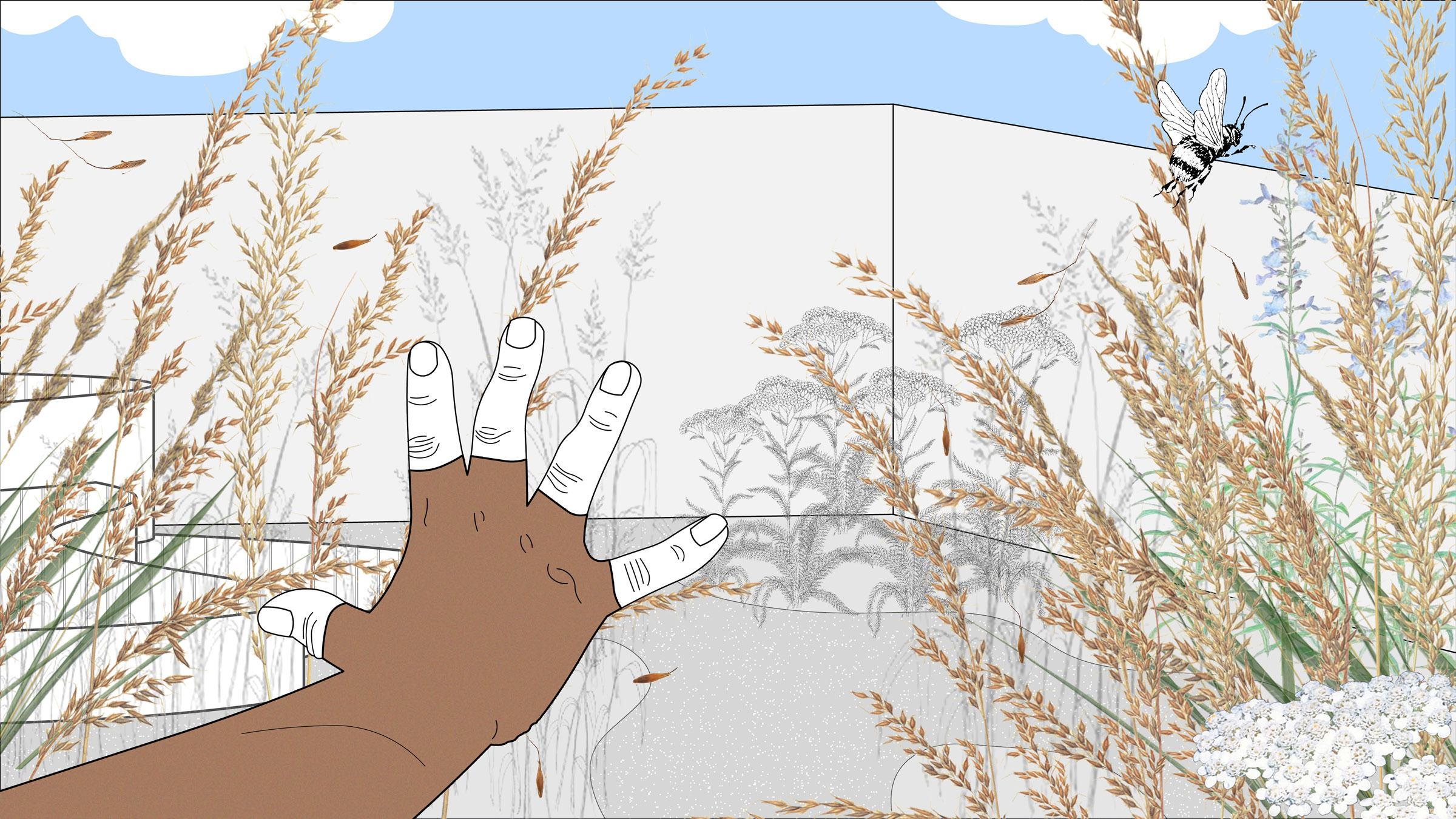

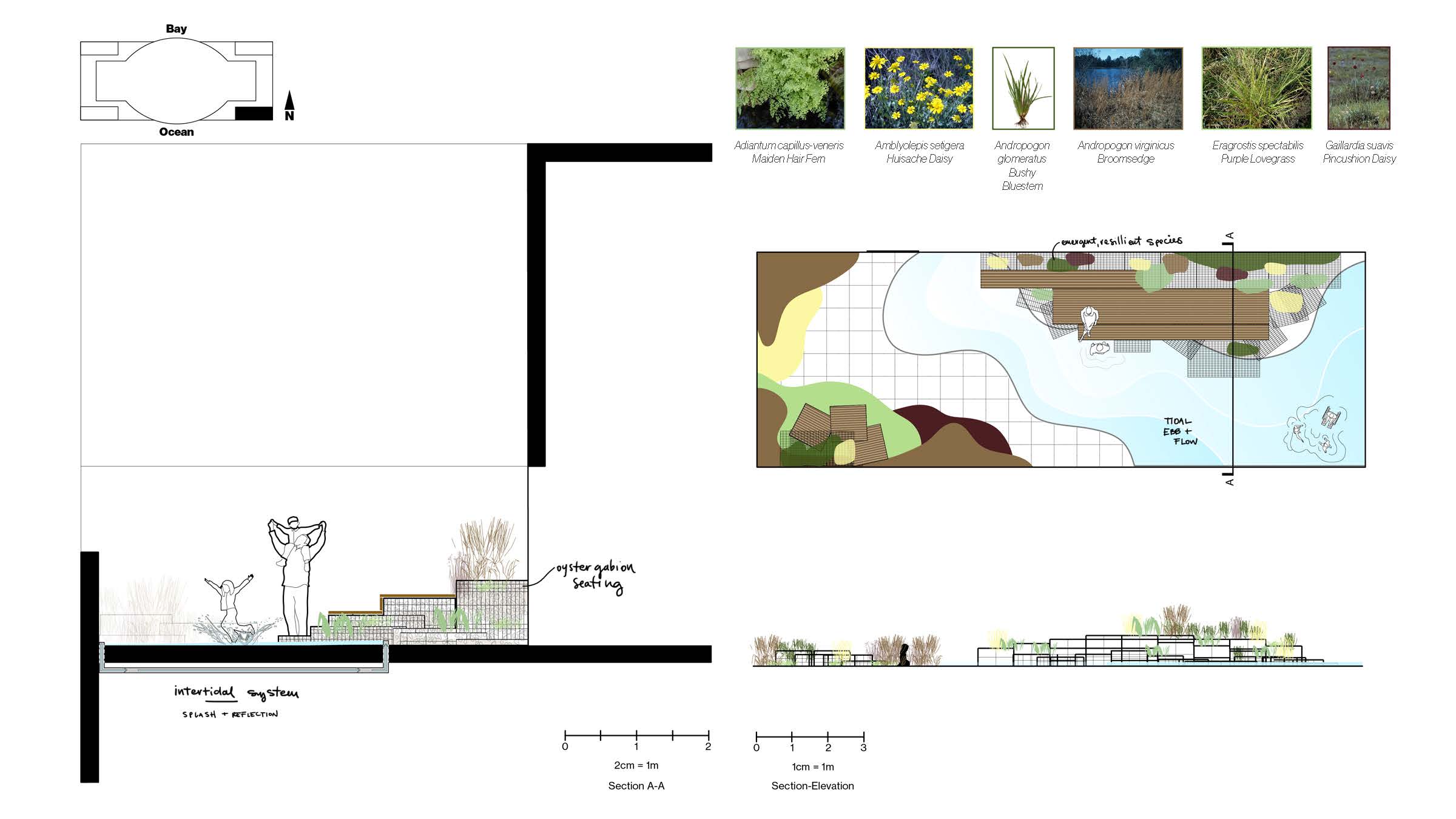

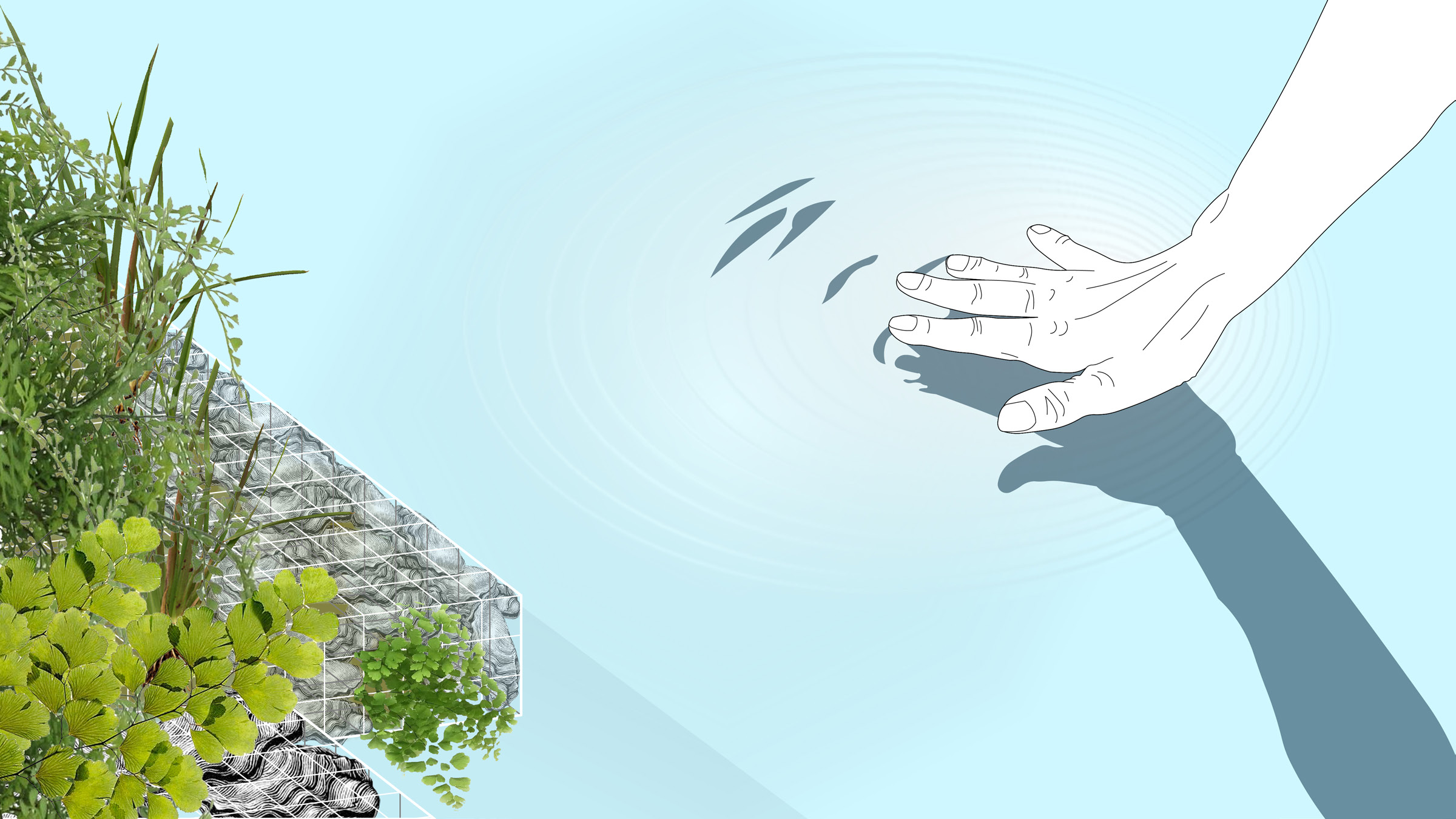

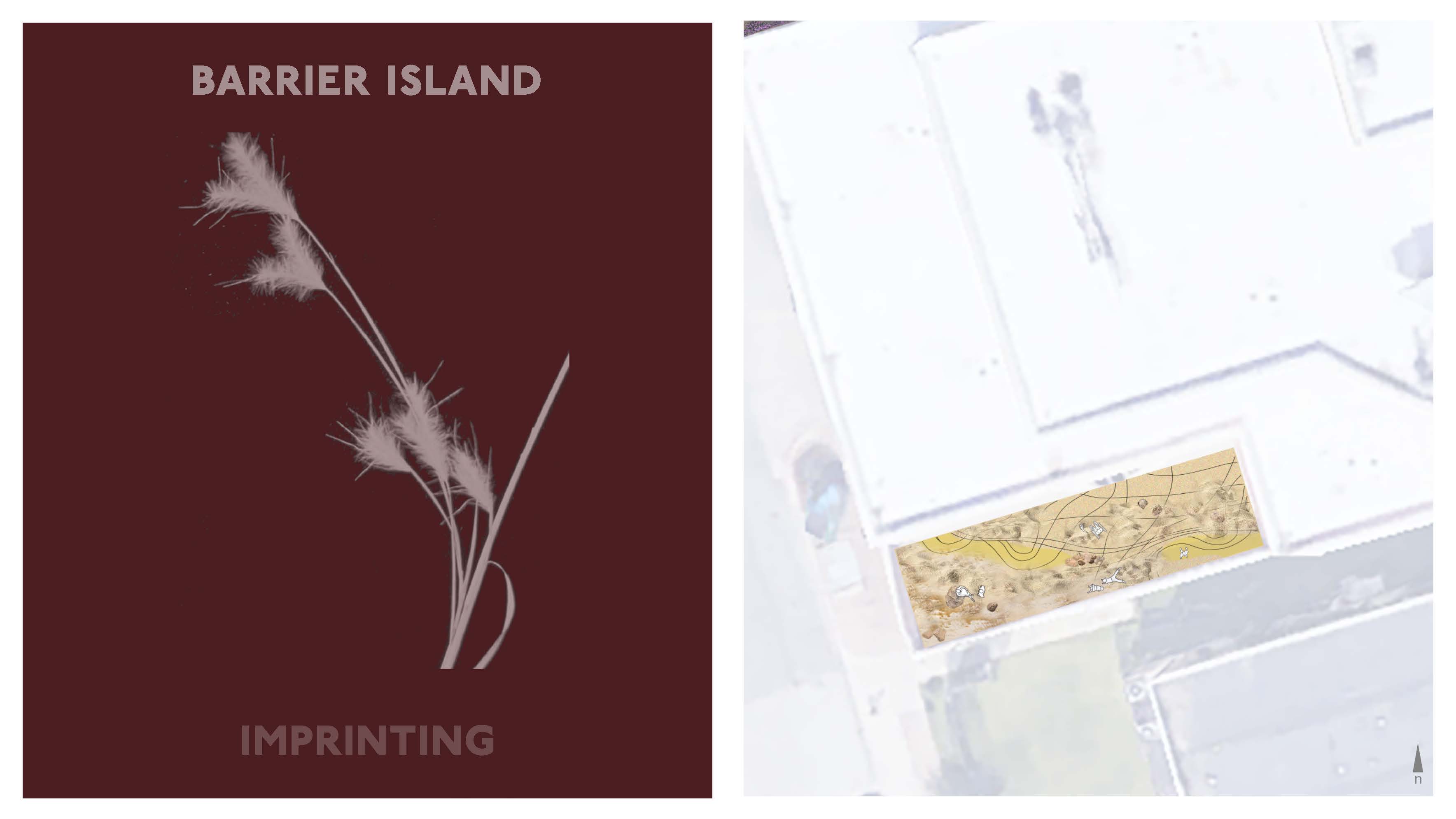

This project builds joy and respite across four terrace designs at Shriner’s Hospital in Galveston, Texas as a means to offer the burn unit a place to get lost, play, and explore the dimensions of touch.

How are the materials that we encounter sensed or felt internally, especially when one’s physical ability to touch, or be touched, is altered? The varied abilities and sensitivities that someone may have opens up new ways for designing for or spatializing touch.

I approached the Galveston Bay Foundation who work around the Houston area, about partnering on a project that addresses deepening their methods of engagement with folks around the bay. We identified a partnership that was on the edge of flourish. Shriner’s hospital for children, located 40 minutes south of the GBFs main property, is a world-renowned research institute specializing in pediatric burn research and recovery. Shriner’s had reached out to GBF a year or so ago and the partnership never got off the ground - so we are using this opportunity to build a long-lasting relationship between the pediatric burn unit and the GBF.

To kick off our engagement and learn more about the two partners, I hosted an hour-long visioning session on Miro where we set goals, learned a great deal about the process of healing, how they value the work they do, and discussed some priority needs for the patients and families.

These diagrams were used to walk through the reconstruction process which begins at the ICU. Note: The designs that emerged from this process were curated for the ‘reconstruction phase’ in order to meet the patients and families where they were at and offer a space of respite and joy.

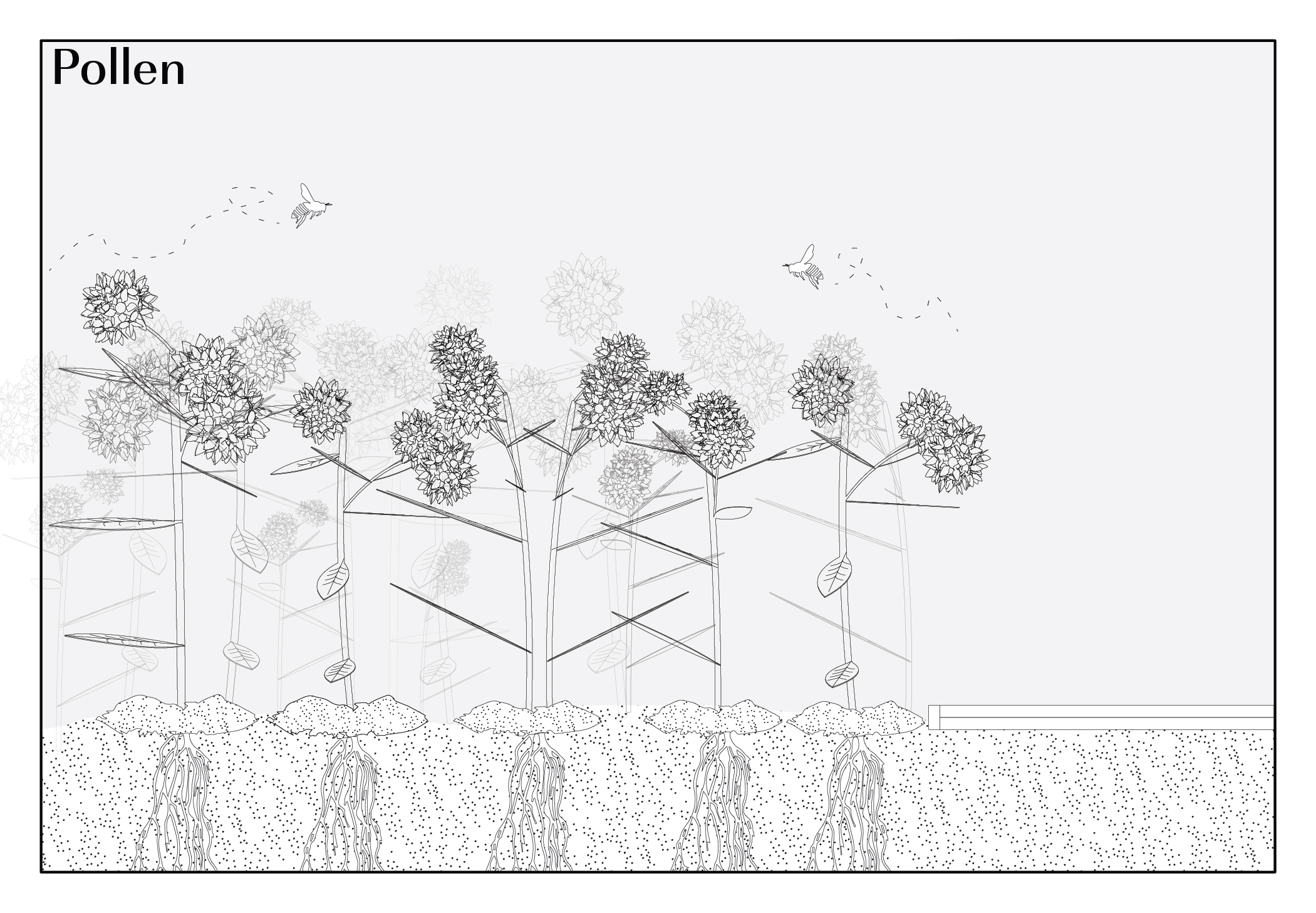

I wanted to challenge and expand upon the breadth of how we understand these dimensions of touch that can be explored for people with altered sensitivities that often present both internaly and externally. The first step was to identify four different dimensions of touch that relate to four sites where the designs play out at the hospital. Then, to tie this sort of “ meta-concept” to something spatial and material, four different ecologies from around the bay were selected that inform the four designs.

The process of healing is not a linear one. The external and internal sensitivities that are altered not only by traumatic events, but our everyday existence should be honored in the process of design.

︎︎︎

Restful Deposition

Advised by: Professor Jill Desimini

Collaborators: Chelsea Kashan, Chloe Soltis

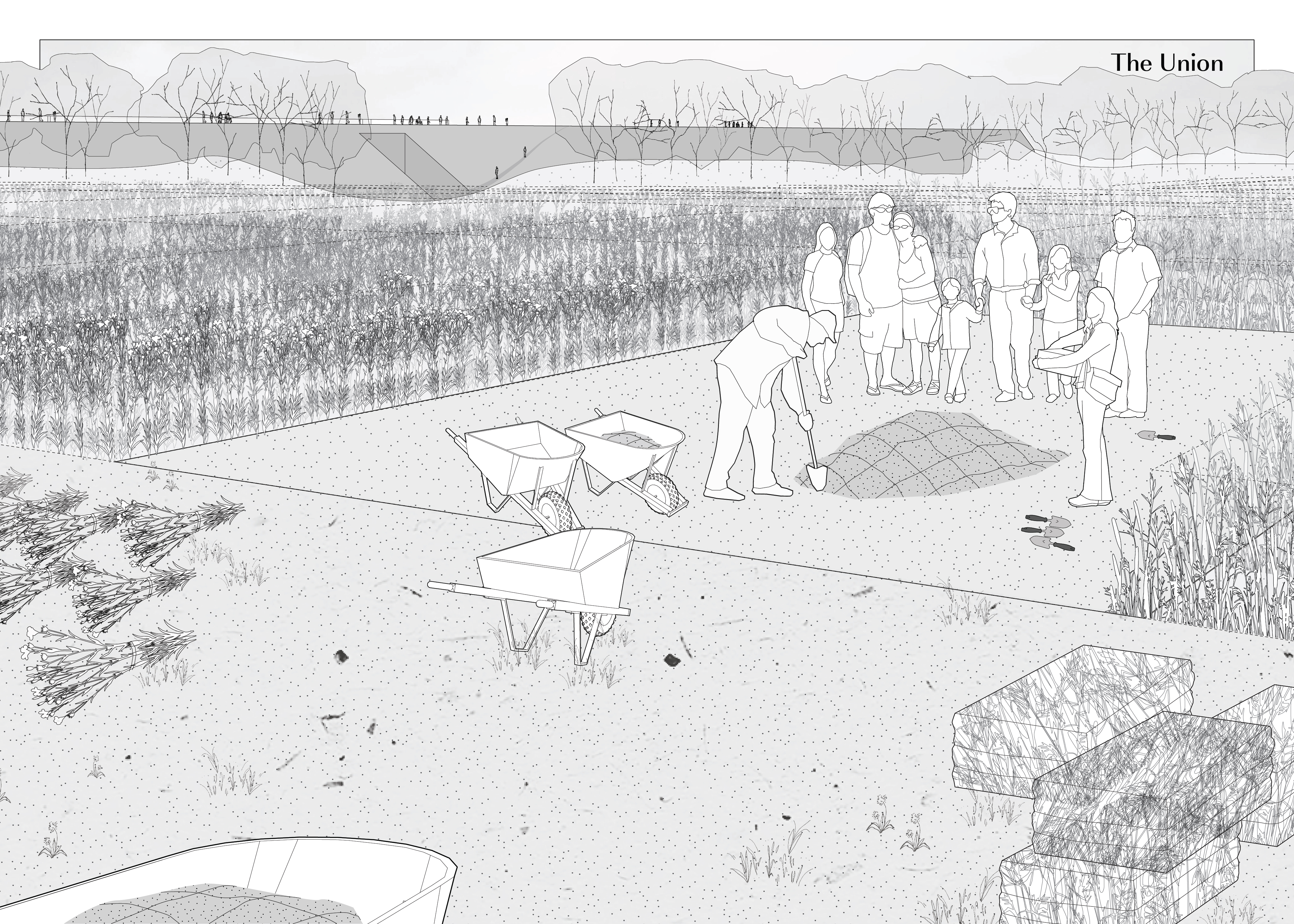

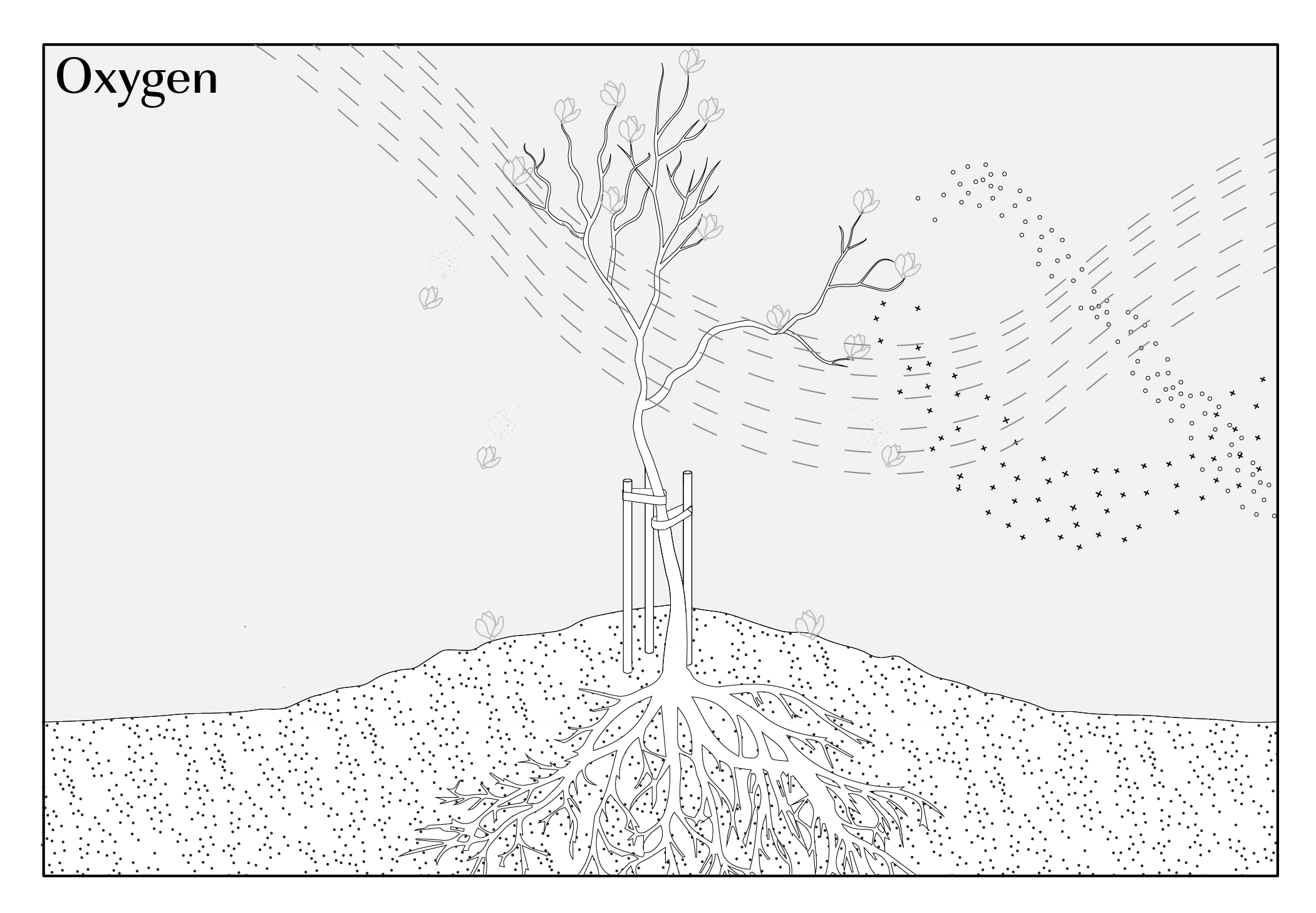

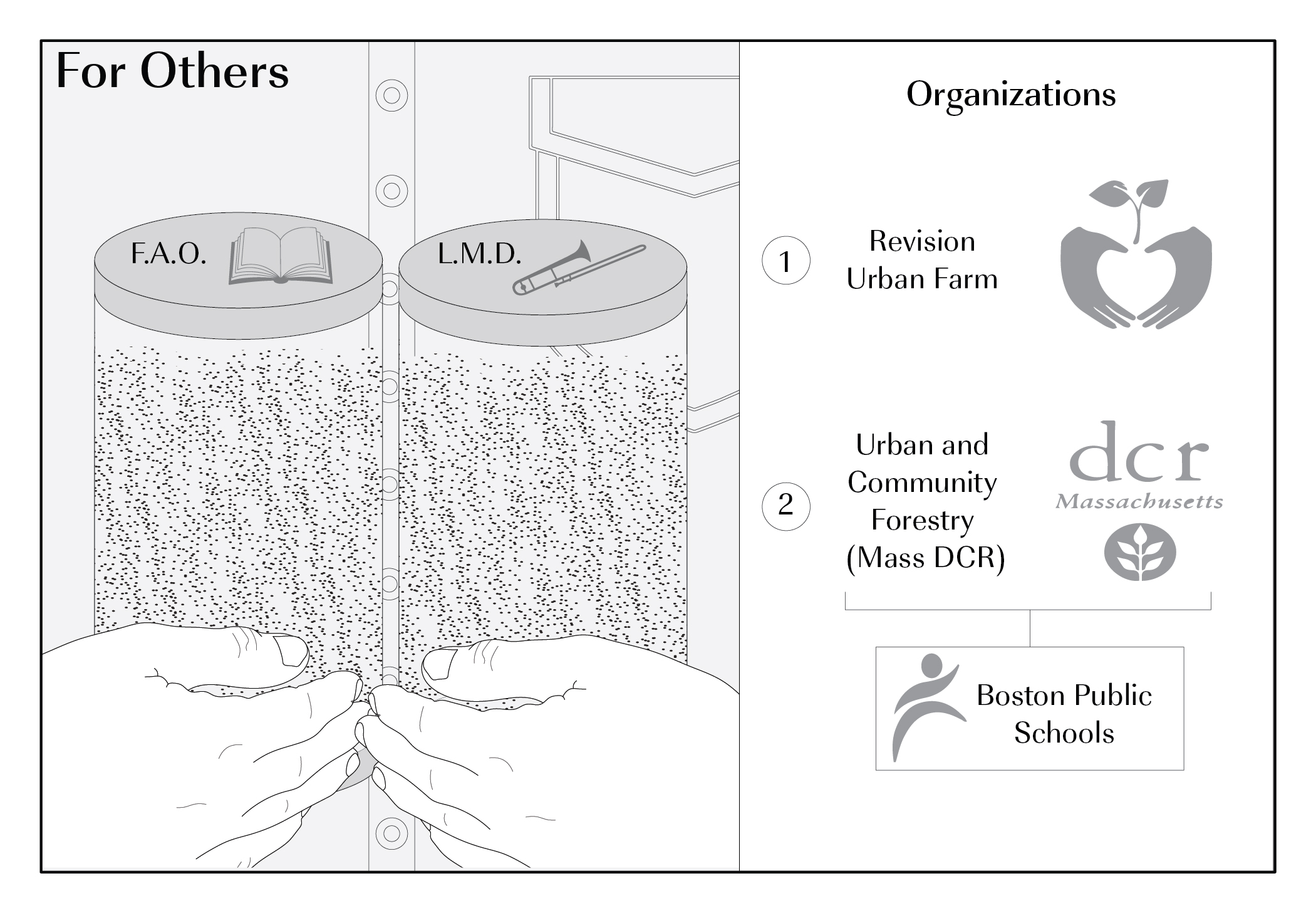

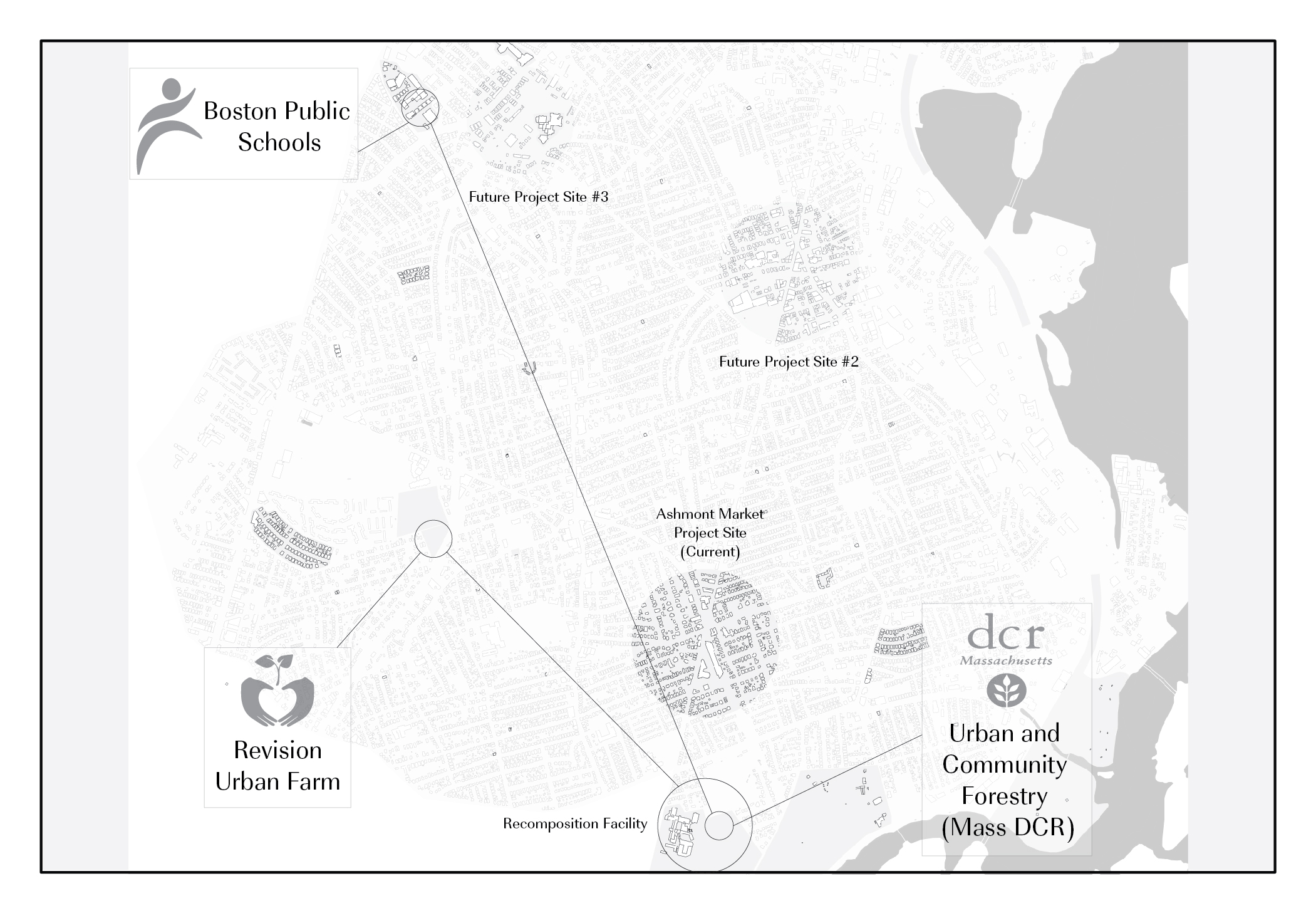

By 2050, Boston, Massachusetts will be out of space to bury their dead. This emerging underground housing crisis had led us to propose a project that builds land in Dorchester.

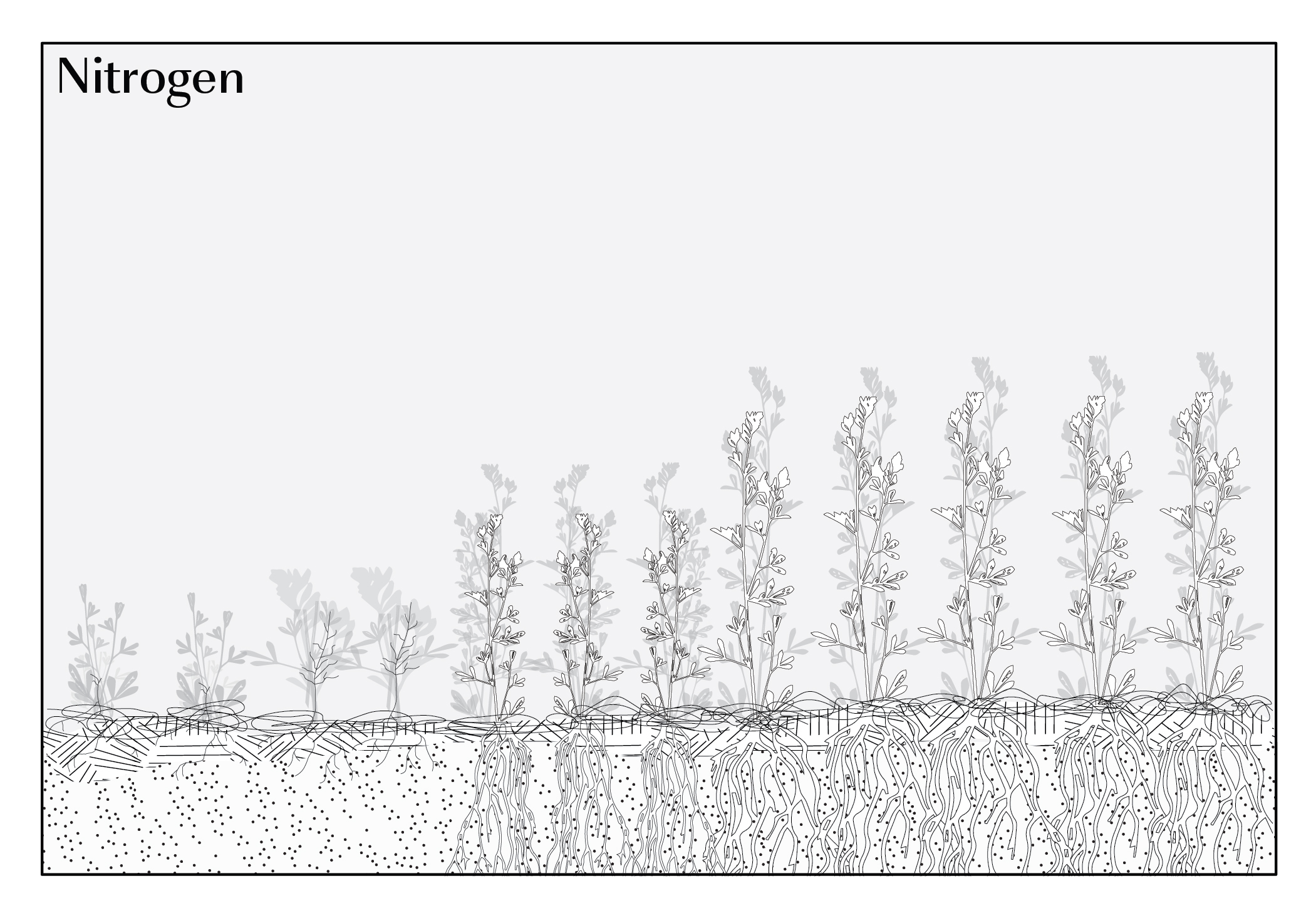

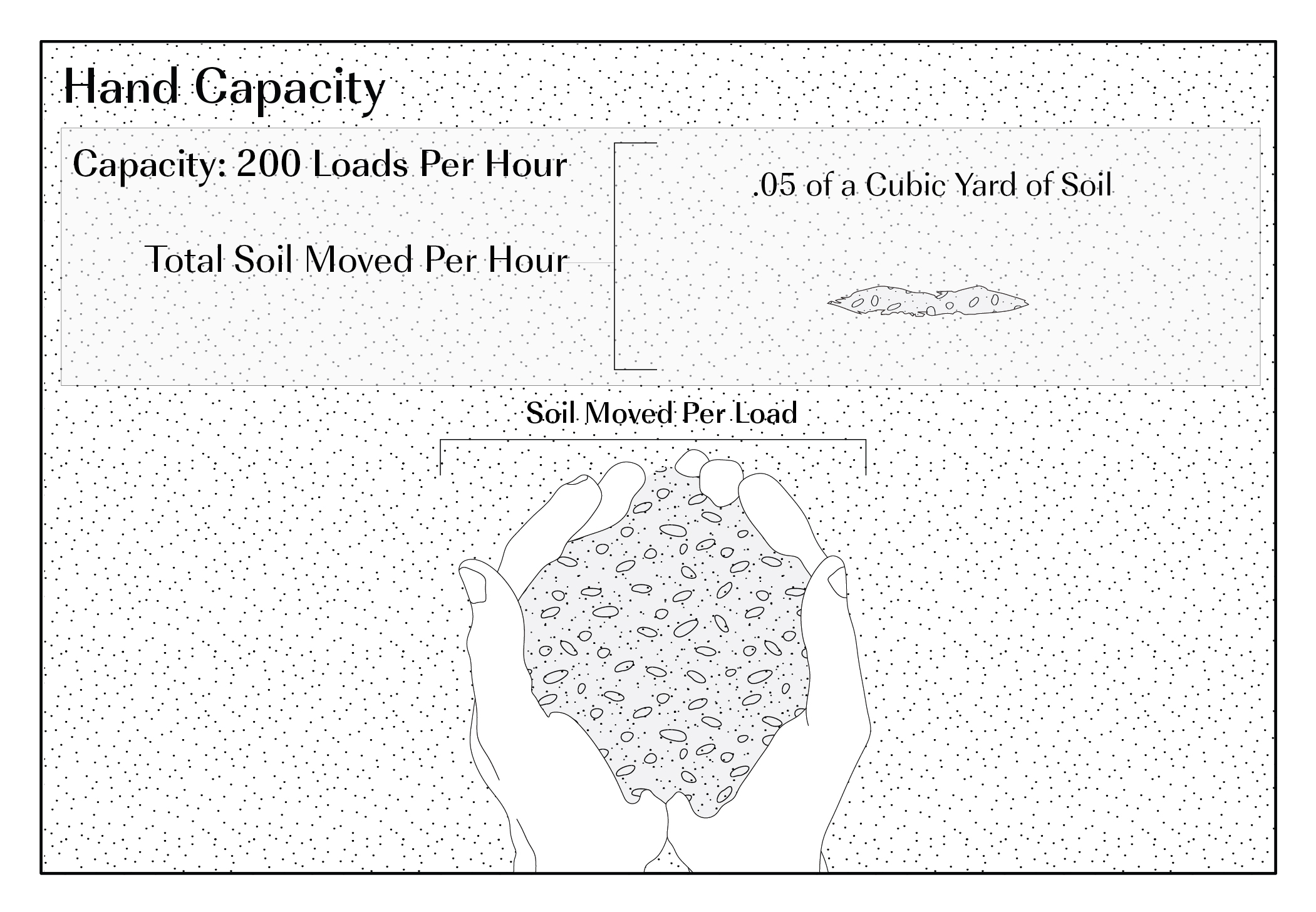

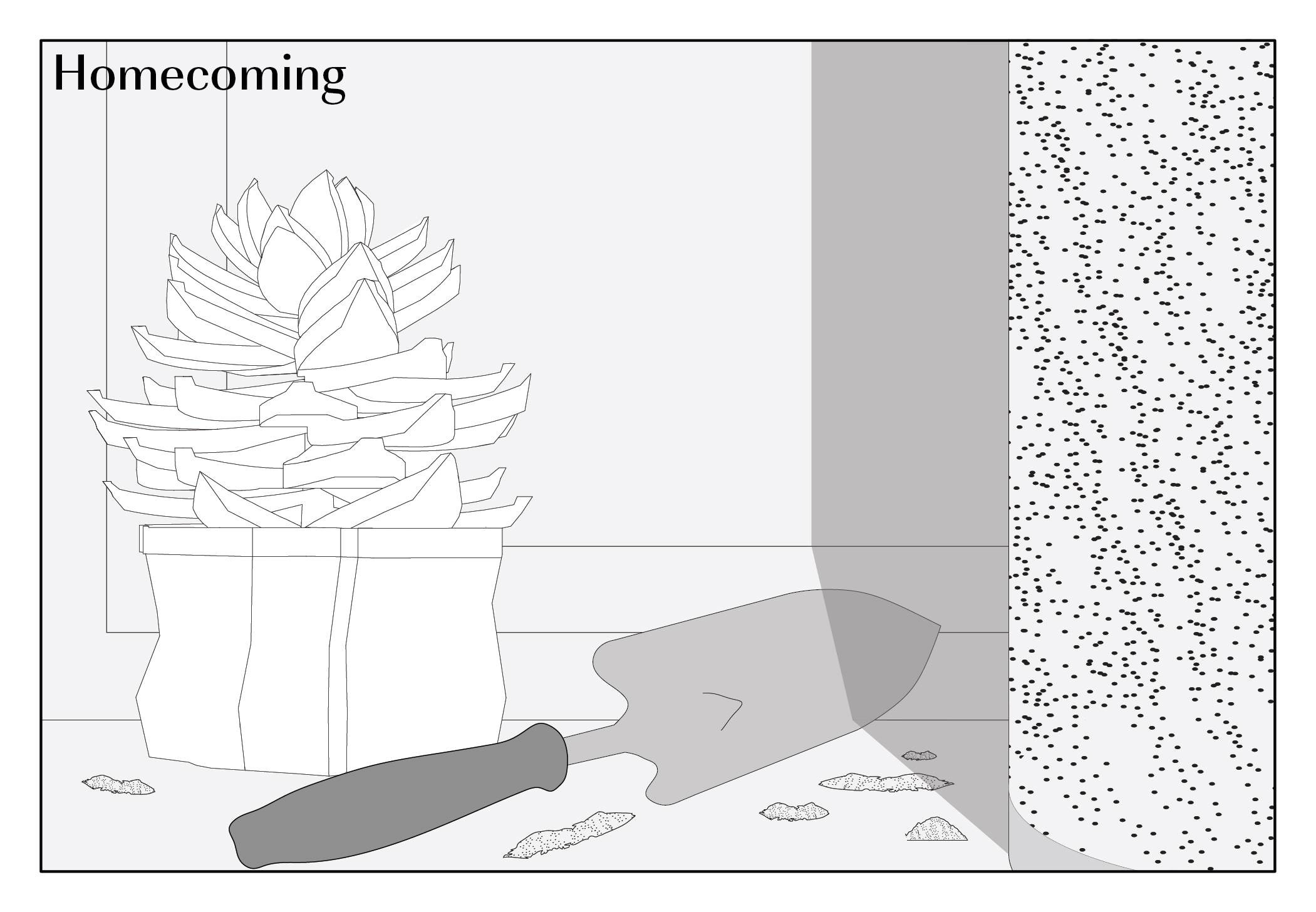

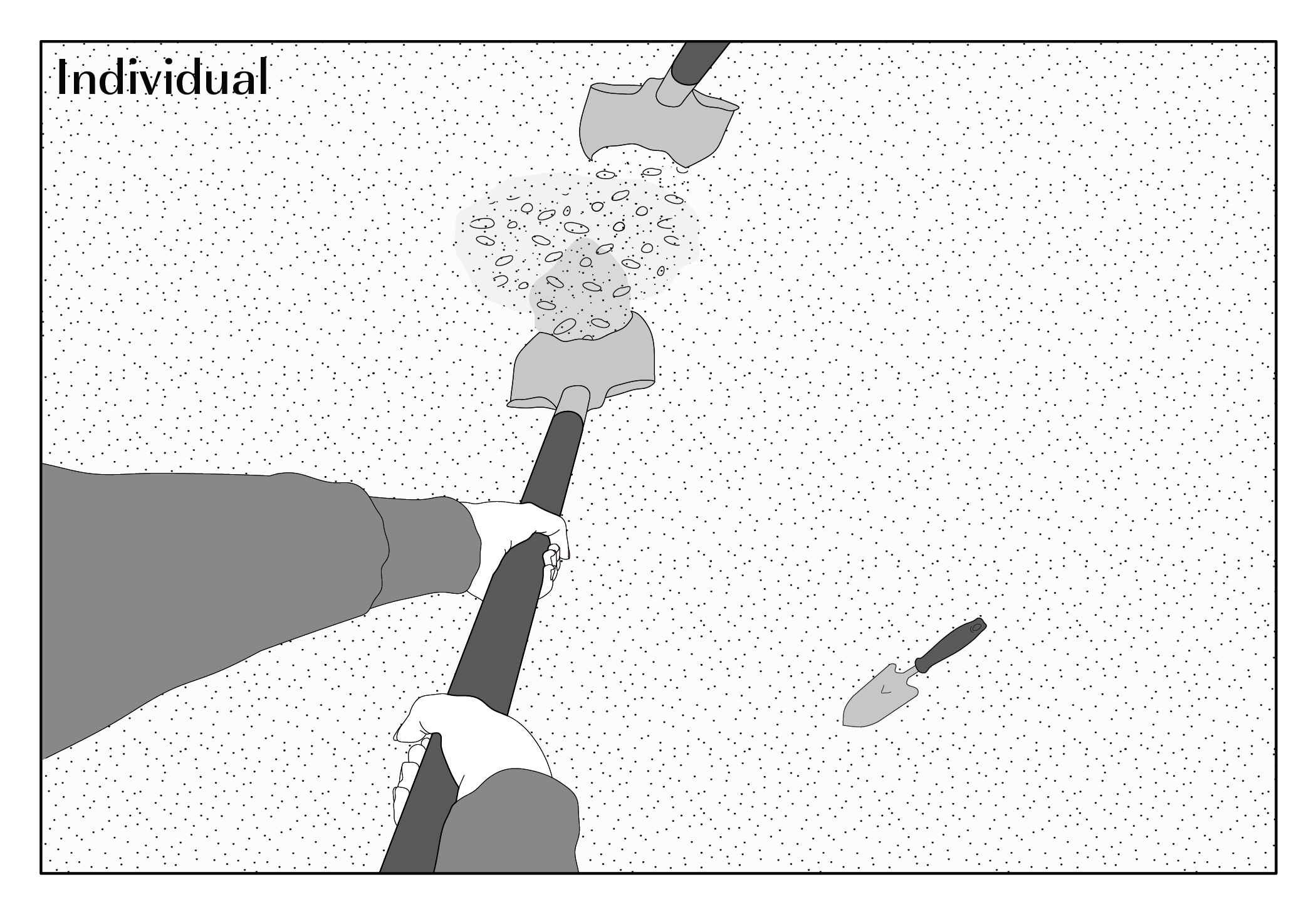

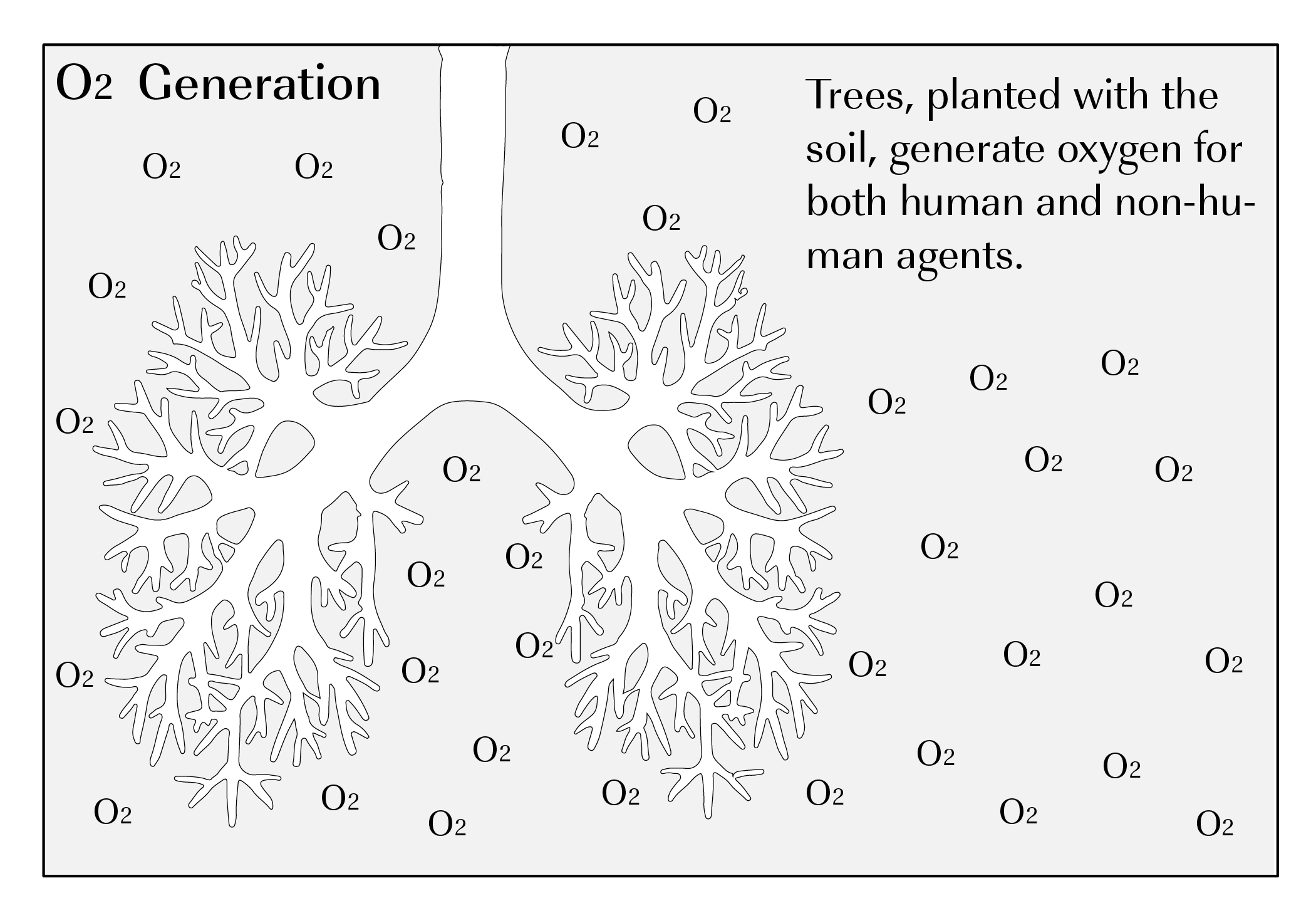

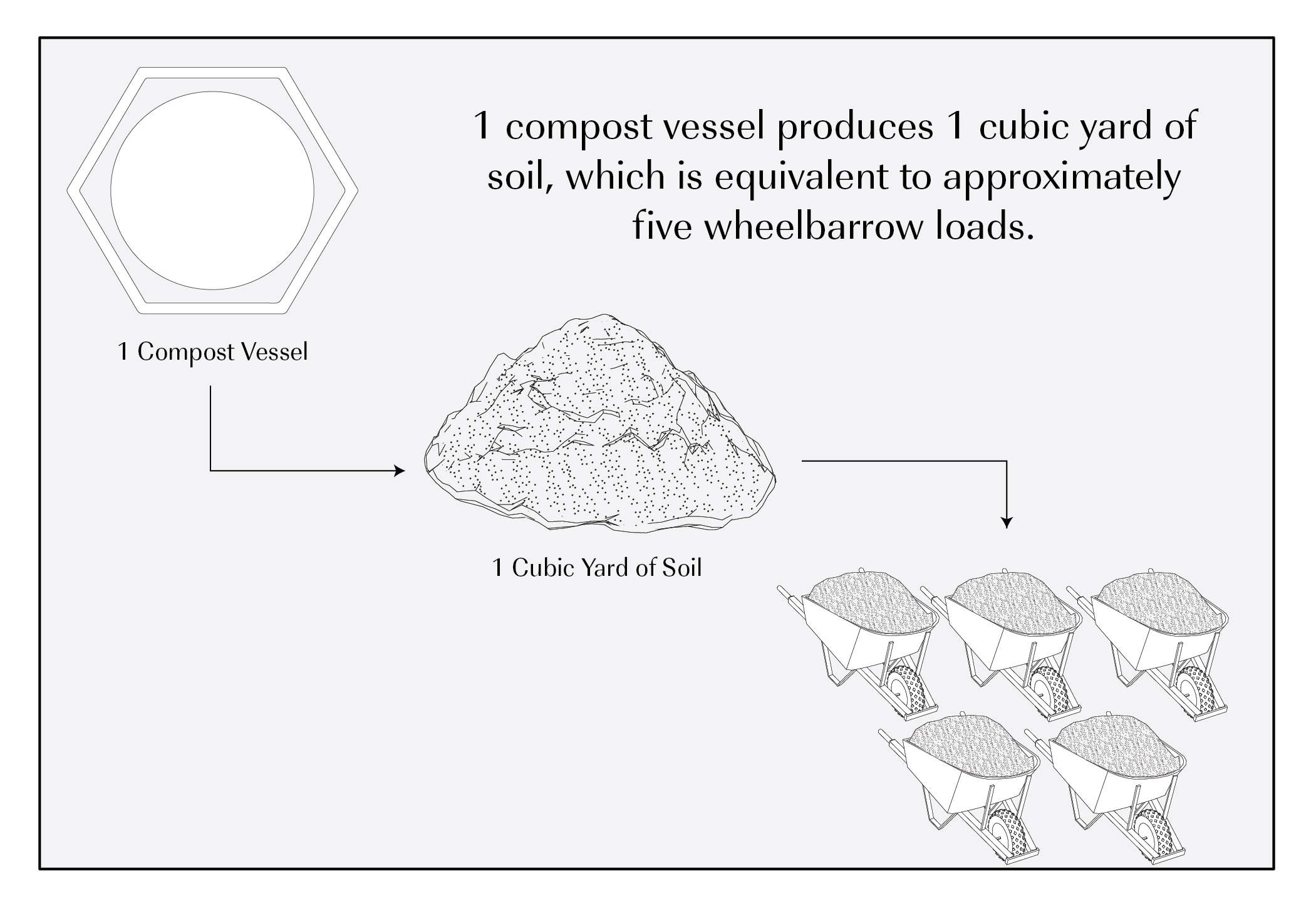

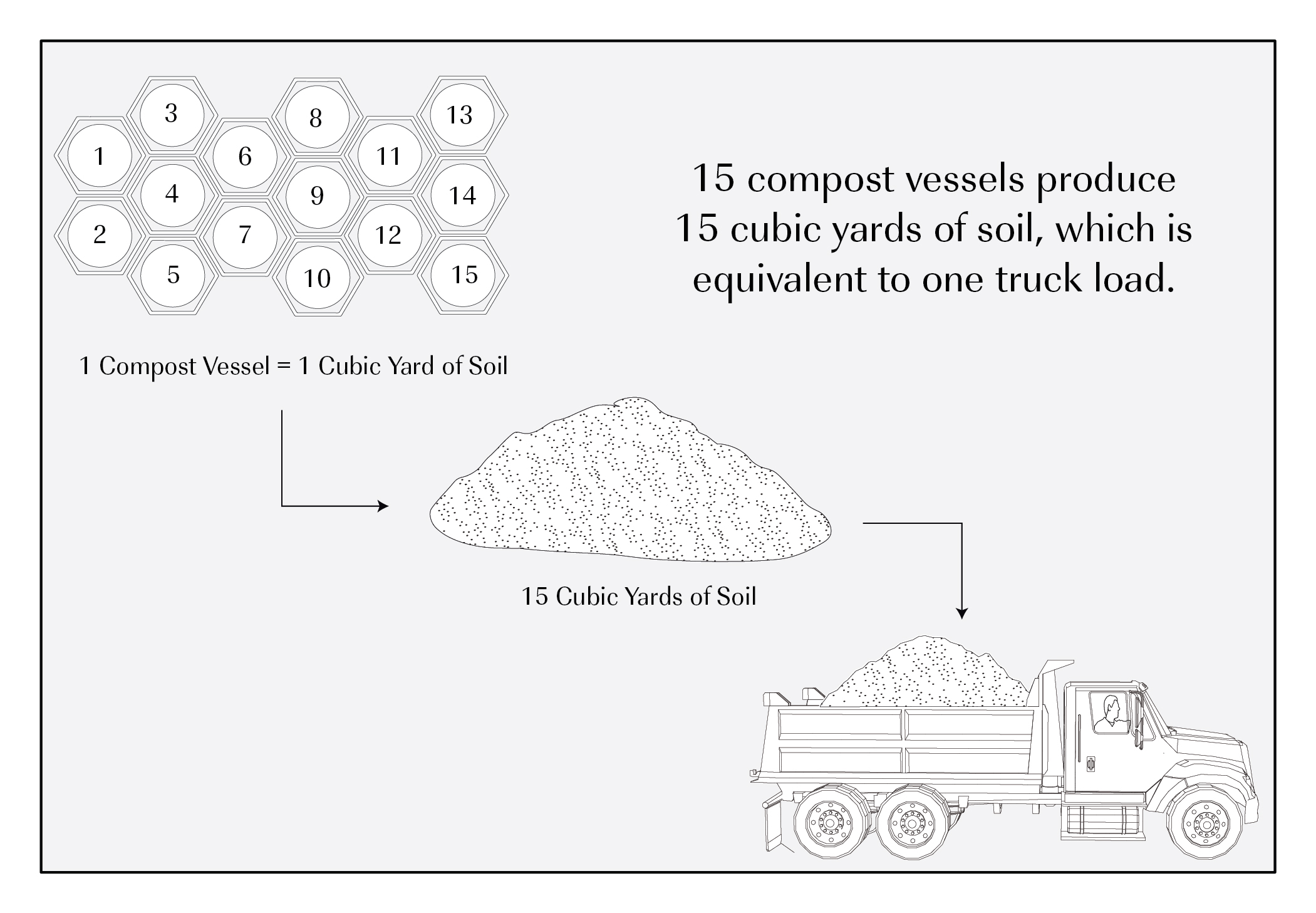

We adopt a burial practice that transforms the human body into roughly one cubic meter of soil. This rich soil will be spread and piled at strategic points around the city. These mounds have their own individual capacity to hold moisture, vegetation, and memory, and represent a restfulness that accumulates differently.

How might reading the depth of urban accumulation, with its multifarious capacities for erosion and compaction, history and memory, guide a new geologic layer for the city? We foreground these layers of accumulation that influence how to build land with the city, its people and its deceased, and with the tiny squiggly things that live within it.

This project adopts a method of burial that does not take space, but rather, contributes to the deposition of memory, history, bacteria, and culture that merge with the layers of Dorchester’s soil.

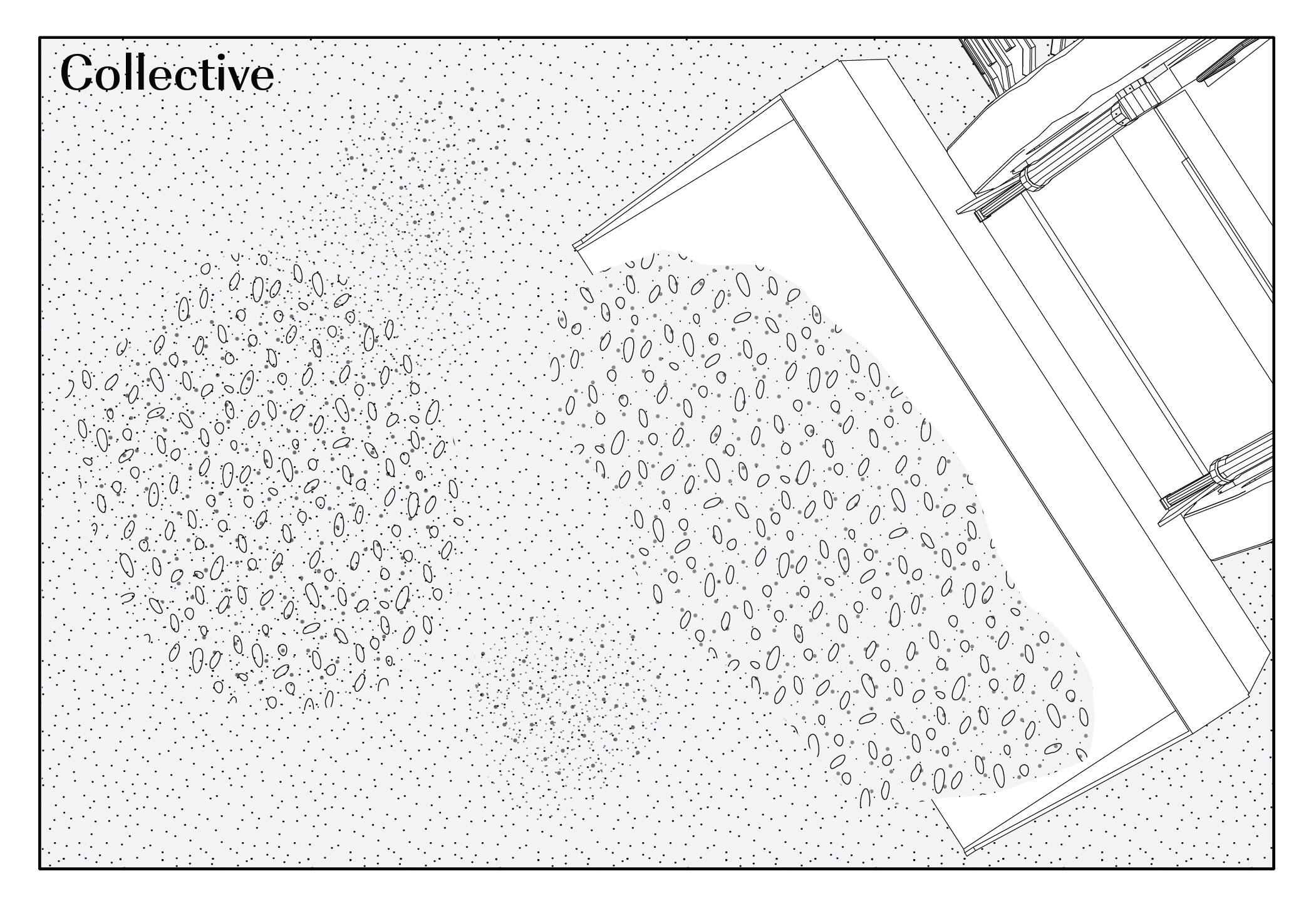

We situated our two main project sites among the existigng network of cemeteries in Dorchester. At these sites, we explored the poetic and productive application of the soil that, unlike the cemetery, activate the surrounding streets, businesses, and communities through the design of a memorial plaza and market and through the growth of specific crops at the scale of an urban farm. We are taking the cemetery from outside the city, seemingly bound and static, to something embedded in the pulse of the city.

Although these play out two different spatial expressions on how to pile and spread this soil, we see restful deposition as a distributed network that can transform the city through a process of individual choice-making - one that builds back urban soils and results in the formation of collective memory.

CHOICE CARDS

The decision of how one rests relies on a set of choices. These choices are the main drivers for how these sites evolve over time and have been distributed into four strategic selections: Materials, Soil Movement, Ceremony, and Microclimate. Each selection has a set of cards that have spatial and material implicationsand when combined produce not only a unique place of rest for the individual, but a new geologic layer benefitting the collective.

To reiterate, we are proposing a process that builds land in Dorchester as a means to center death in urban life, yet still acknowledge that the decision of how one rests remains an individual decision. This decision has the capacity to build land, integrate and accumulate soil, reprioritize urban streets and give back to the city, representing a restfulness that accumulates differently.

IN-PERSON TESTS

COVID LOCKDOWN ZOOM FUN

Poem by Aracelis Girmay titled Elegy

What to do with this knowledge

that our living is not guaranteed?

Perhaps one day you touch the young branch

of something beautiful. & it grows & grows

despite your birthdays & the death certificate,

& it one day shades the heads of something beautiful

or makes itself useful to the nest. Walk out

of your house, then, believing in this.

Nothing else matters.

All above us is the touching

of strangers & parrots,

some of them human,

some of them not human.

Listen to me. I am telling you

a true thing. This is the only kingdom.

The kingdom of touching;

the touches of the disappearing, things.

︎︎︎